He’s always been like a real character, almost like a mate to me

Category: Featured

Reading Elly Griffiths, inspired by this blog

I’m now on The Chalk Pit which is the ninth and have no intention of stopping

Elly Griffiths talks about misdirection, redemption and forensic botany …

I’m certainly attached to Ruth and Nelson in a way that means I can’t ever really just treat them as words on a page

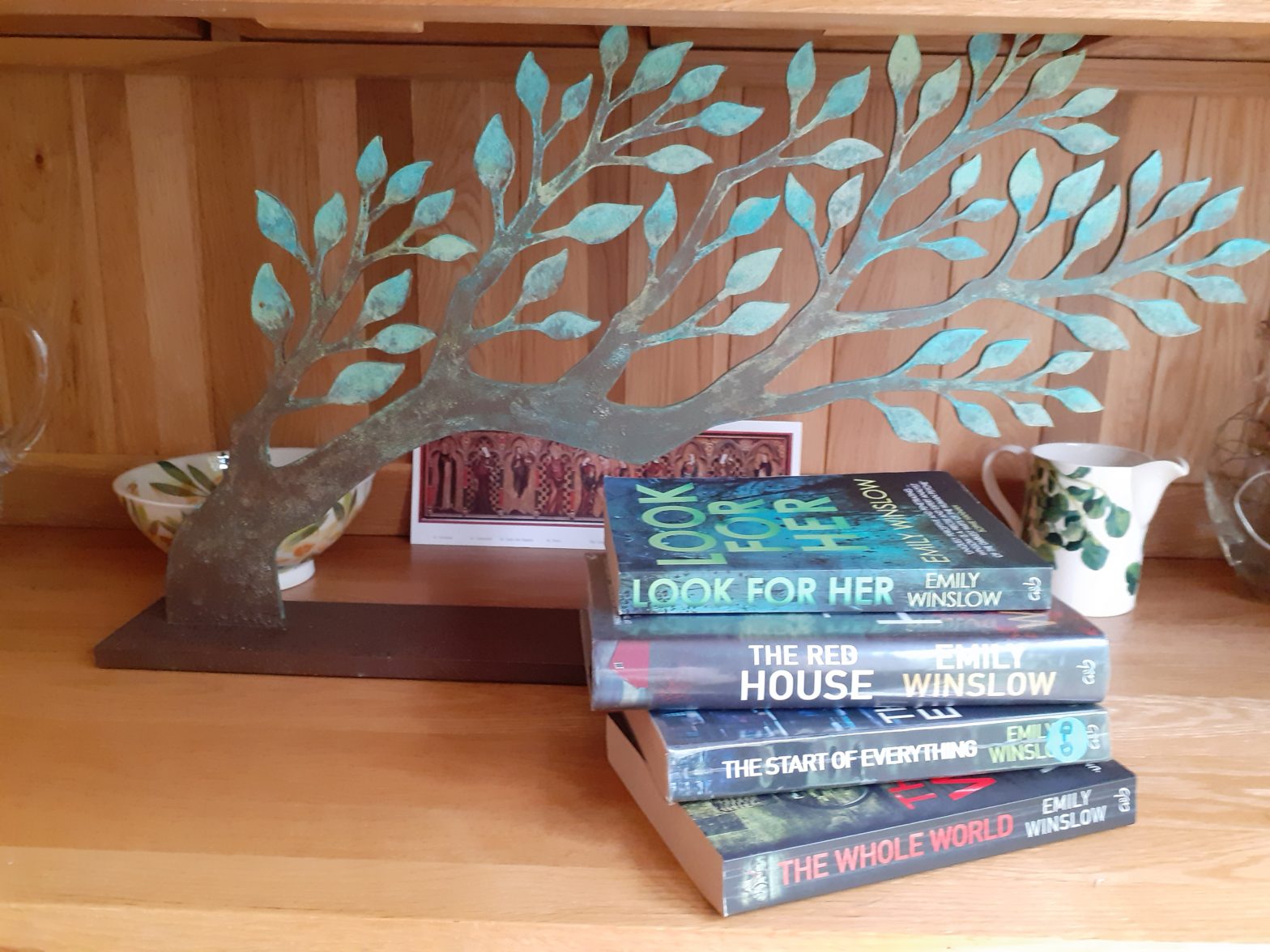

Emily Winslow, a unique and original voice in crime fiction today

Emily Winslow, with her multiple narrators (reminiscent of Wilkie Collins’ great detective novel of 1868, The Moonstone) has introduced an unusual and distinctive voice into the world of contemporary crime fiction.

Emily Winslow talks about writing crime fiction

I think of myself as a crime writer, but with the very broadest definition of crime.

Alison Bruce talks about detective fiction

My mum read things like Agatha Christie and British, cosy crime, but then she tended to watch American crime on the TV. Dad would sit reading his book, being very disapproving.

I know I have books that I will never open, and on a few occasions I’ve bought them just because they are beautiful to look at!

I have at times used audiobooks as company in the middle of the night, but apart from that, I have just picked the books that look like an interesting mystery.

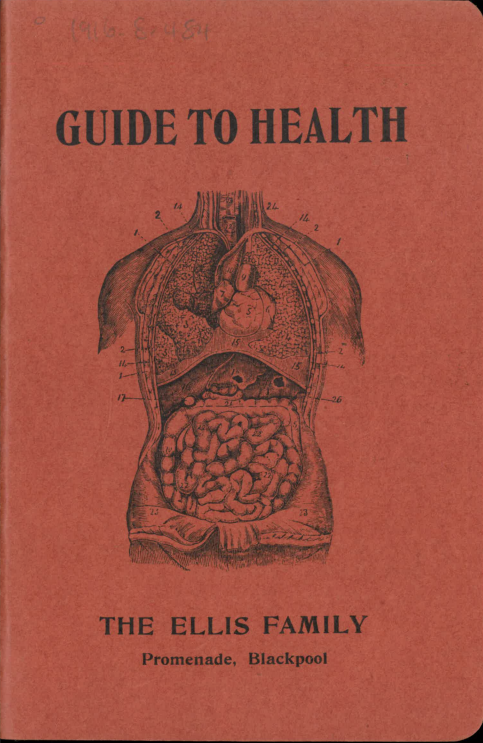

A Family of Phrenologists

When we think of seaside promenade attractions, such as fortune-telling, palm-reading and so forth, we tend to imagine stripey booths and bead curtains.