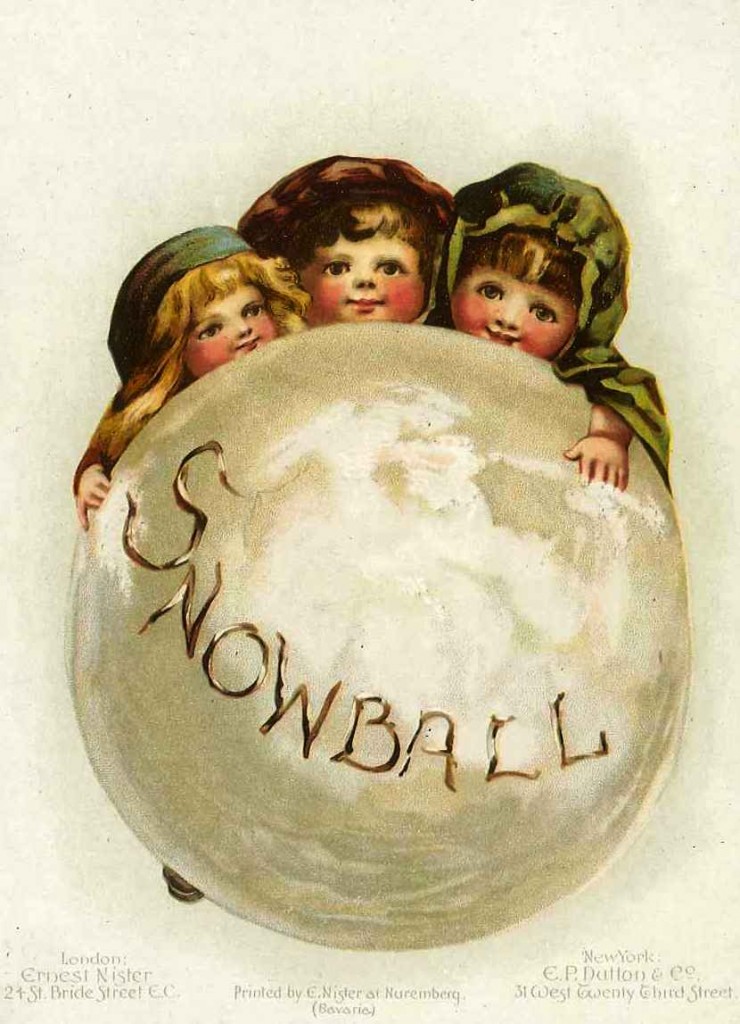

The children had been up early in the morning, and beginning to roll a snowball about they very soon saw that at every roll they gave it got bigger and bigger, and at last got so big just by the cottage door that they couldn’t move it, and then it stood right in the way,…

Category: Featured

Third Day of Advent

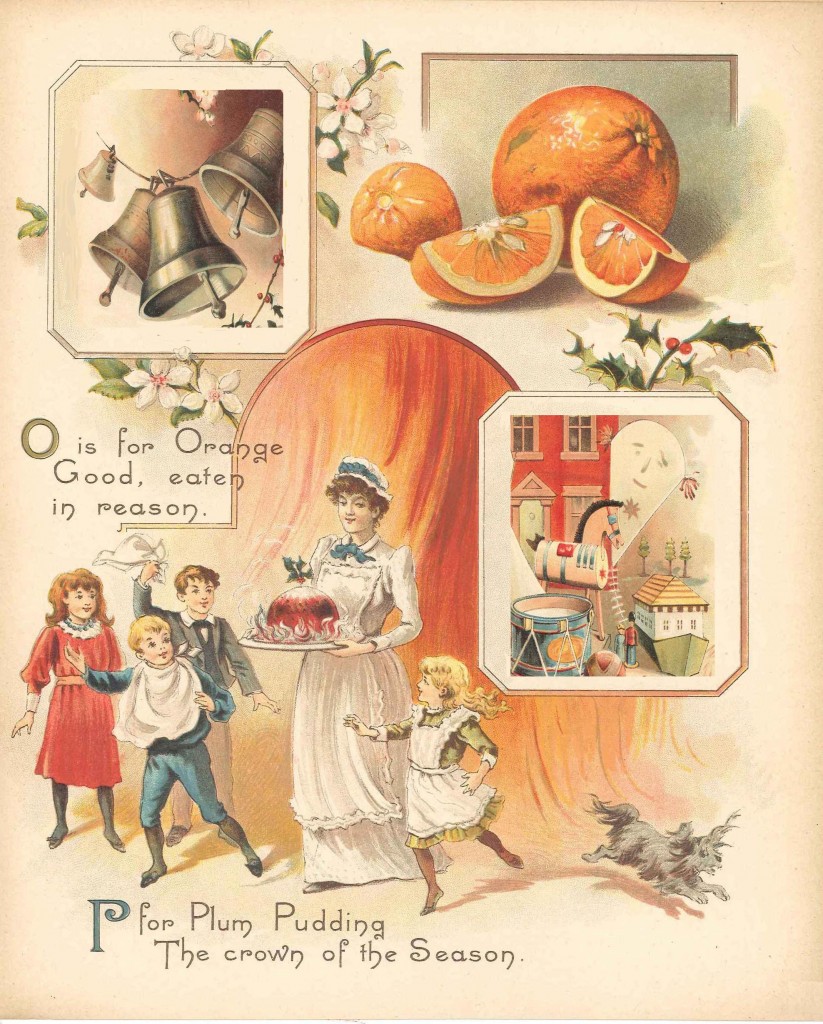

O is for Orange – good, eaten in reason, P for Plum Pudding, the crown of the season. From “Father Christmas’ ABC” illustrated by Alfred J. Johnson, published by F. Warne & Co., 1894 I love the bright, cheerful warmth of this illustration – I can almost smell the tangy scent of those oranges. Is…

Second Day of Advent

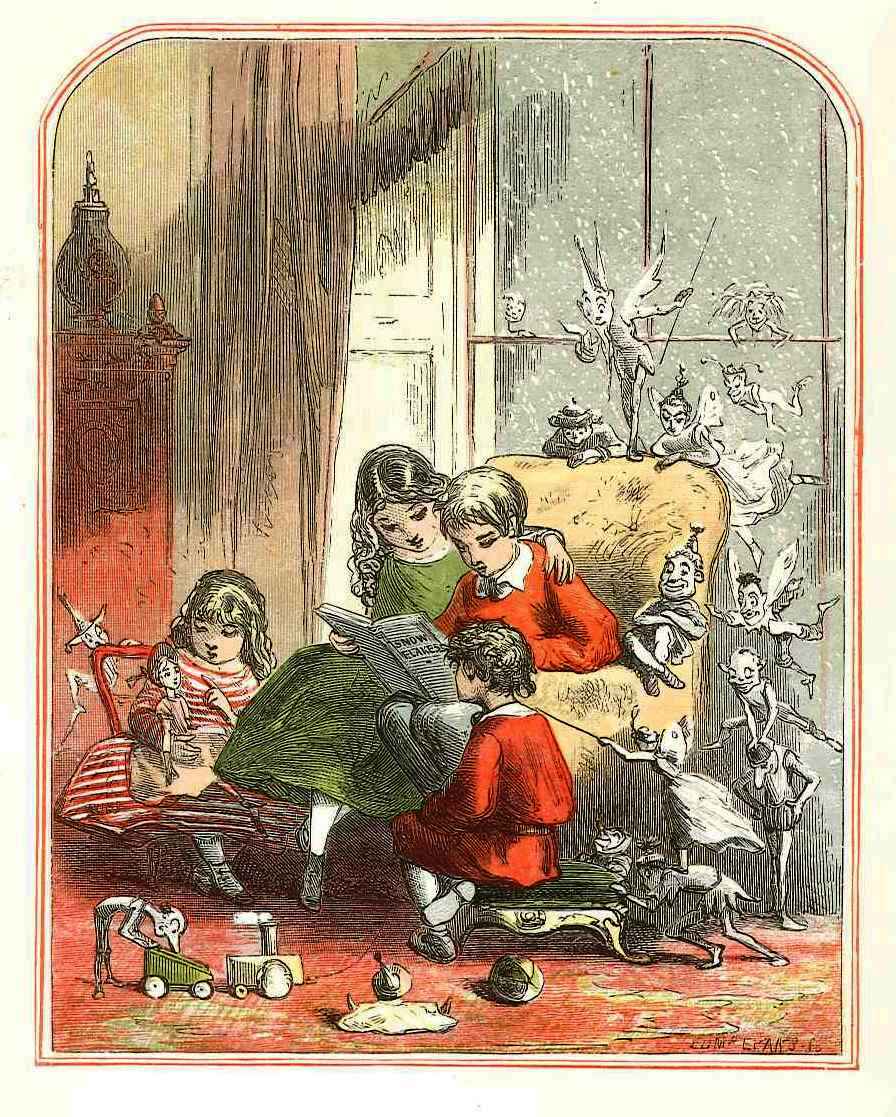

Come to the window, little folks, And read these tiny Story-books! From ‘Snow-Flakes and the Stories they Told the Children’, by Matilda Betham-Edwards, illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), published ca. 1862 This is my personal favourite, it’s by Phiz, Dickens’ illustrator. I love his pictures full of charming, quirky detail. The elves in…

First Day of Advent

Tower Treasures Advent Calendar

For Truth’s Sake

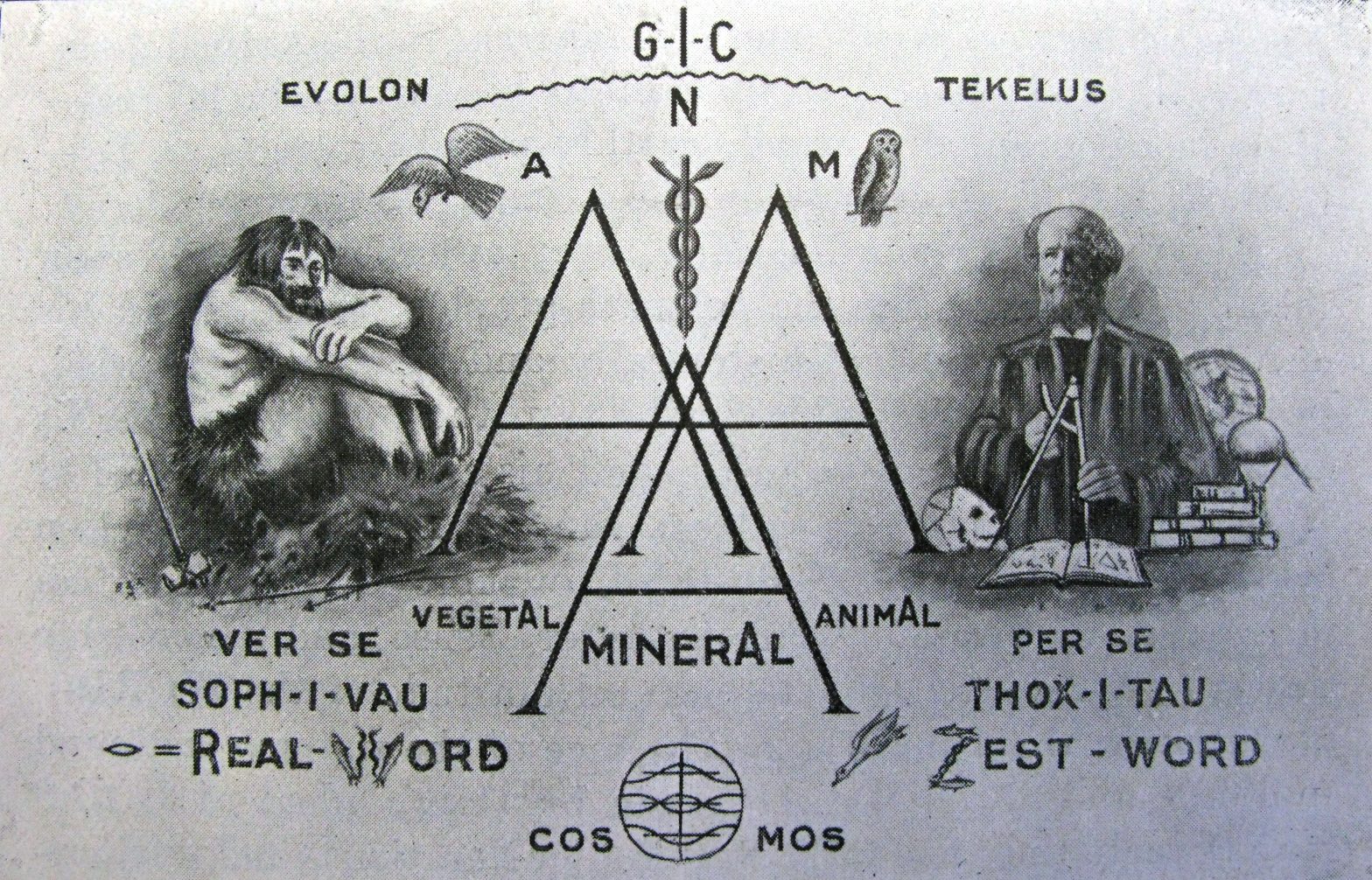

It is hard to explain the sensation of reading something in your own language and not having a clue as to its meaning

People see what they want to see

David Henty is an extraordinarily gifted artist who paints copies of paintings by well known artists, such as Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Monet, Modigliani, Basquiat, Lowry, Rockwell, Sickert, Picasso and many more. Is this art forgery? Not really, because David is transparent about his paintings, signing them on the back and selling them openly as copies –…

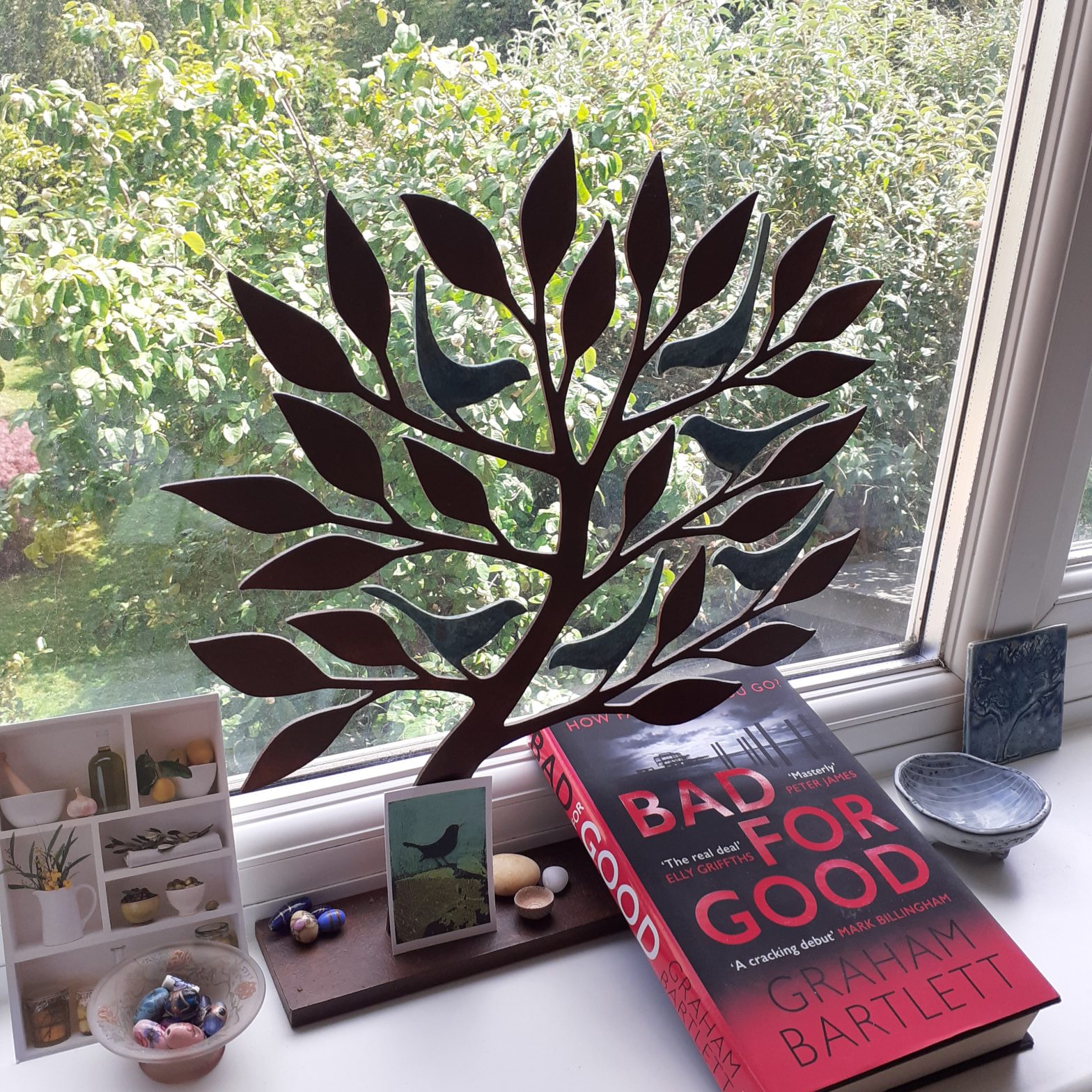

Graham Bartlett talks about his second calling

I did actually want to explore something about how it was different for women both in terms of what they go through, but also what they offer

Graham Bartlett, bestselling author and advisor to crime writers, talks about his police career

All I ever wanted to do was join the police

Elly Griffiths talks about life under lockdown in her latest Ruth Galloway book The Locked Room

I’ve always wanted to write a locked room mystery, and here we are in a locked world

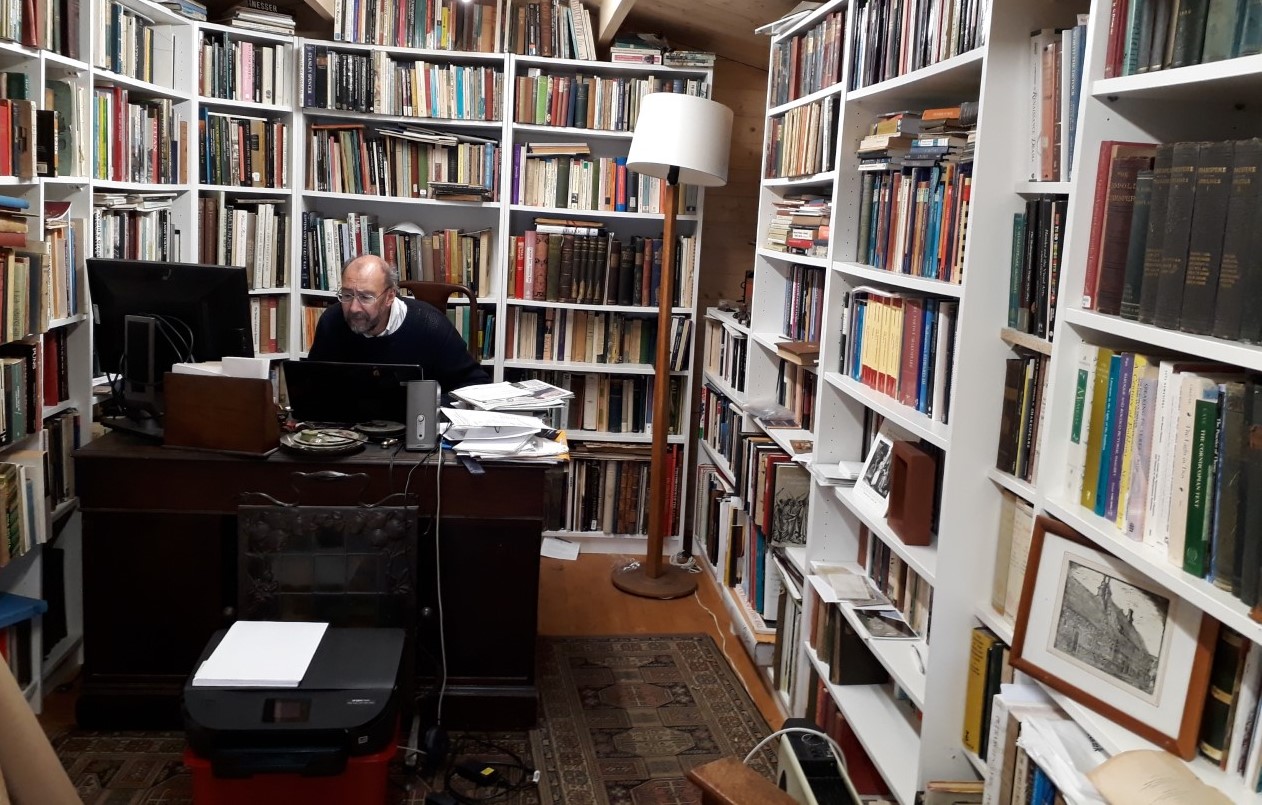

Professor Stuart Sillars talks about illustrated fiction between the wars

I came to think of these magazines as very important survival mechanisms, keeping people together in communities