It struck me while reading the chapter in which you discuss illustrations in detective fiction, that nowadays we tend to associate illustrations with children’s books, as if we grow out of the need for pictures when we’re adults, and I just wondered when and why this happened?

Yes, I think that’s true. I suppose there are several reasons for this. One of them is that it becomes much easier to lose yourself in the world of fiction if there aren’t pictures. Another is the way that crime fiction has developed, probably from the 30s onwards, it’s become so much more violent that you can’t really make pictures of it.

But I don’t think that you have that same kind of need for pictures from Dickens onwards, where fiction is something that’s read over a much longer period. The reason why Dickens illustrations are so successful really is an accident, because he was asked to take over writing some fiction which was illustrated. If you put in illustrations you actually lose about a quarter of the extent of the story that you’re writing, which immediately means that it can be done much more quickly. And it also means that if it’s coming out weekly or monthly then the readers have more time to get to it, and they can use the images as part of the involvement.

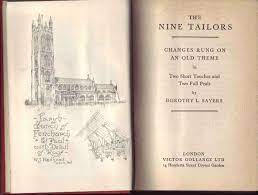

It’s very much to do with the genre really. The first Agatha Christie and the first Dorothy Sayers were actually published as stories in a magazine of fiction, and they were illustrated, but after that it just stopped. But there are a couple of exceptions with Sayers – like the picture of the actual church where The Nine Tailors is set.

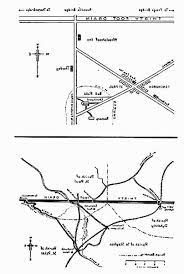

If you look at the frontispiece and the title page, you’d never guess that it is actually a piece of crime fiction, it could be a novel of any kind. You’ve got the church, and a series of maps which draw out the main lines, and the fen ditch at the top, which I find completely incomprehensible. Presumably she knew about all of these things, but whether the illustrator did is another question.

Really it’s a matter of the fact that the illustrations are going to get in the way of reader involvement, and my feeling is that at this period the involvement isn’t so much finding out the author, and the nature and reason for the crime, although that’s part of it, but it’s actually joining into a completely different world from that that’s occupied by the reader. It’s the kind of thing that Queenie Leavis describes as “living at the author’s expense” and a “corrosive habit of fantasy-ing”. But now of course it’s perfectly legitimate to say “Oh, I read this for escapism”.

It’s like the attitude to WH Smith, who actually brought reading to a much wider public by selling newspapers and popular novels on railway stations, but intellectuals thought that the whole of civilisation was being undermined by this, didn’t they?

Yes, absolutely. Sidney Dark wrote about the “new reader” who he says should be reading Balzac and all kinds of literature, which is really quite endearing in a way, it’s as if people have been fighting in the trenches for four years, leap out of the trench and say “Right, now I can get down to some serious Balzac.”

But this attitude, as you say in your book, lacked understanding and kindness, didn’t it, as those who needed escapist fiction were leading very different lives from those who deplored it, weren’t they?

Absolutely, yes. And the “new reader” that emerges is the reader who is concerned with practical skills, which come out in magazines for men, and other things which will advance them in skills, like the Everyman editions, which have just celebrated their 500th anniversary.

Although illustrations can have a limiting effect for the reader by narrowing down to the illustrator’s vision, what they can do is create a powerful atmosphere, as they do in Sherlock Holmes stories, for example.

I think that’s absolutely right and it’s actually very interesting you should say that, because when I was thinking about what you’re going to ask me, I dug out something that I wrote ages ago. I was asked to do something on the short story, in a colloquium that a friend of mine organised in Oslo, and I wrote something about the Sherlock Holmes stories and their illustrations, and I found that in almost all cases the illustrations have nothing to do with the mechanism of solving the crime, they’re all about the situation.

I wrote mainly about Silver Blaze, which starts off with this wonderful image of the two of them in the railway carriage. And then there are pictures of the horse and various other things, but nothing that will actually help you identify who did it. And that’s more or less the same for almost all of them. So I don’t think that they have much to contribute to the unfolding of what’s actually happening.

But they contribute something else?

They do, they contribute a great deal to the world in which the story takes place, the world of the expensive gentlemen’s clubs in the Wimsey books, and that rather spurious, even in the 20s and 30s, English village, which has much more to do with the novels of another century earlier.

It’s interesting that the deerstalker is the abiding image of Sherlock Holmes, although he was never described as wearing one by Conan Doyle.

Yes, that’s a very powerful impact and it’s something that is very personal to him. I mean not many people wore deerstalkers, or if they did they were, well, stalking deer! But it’s a way of making the central character instantly identifiable, like his enormous cape.

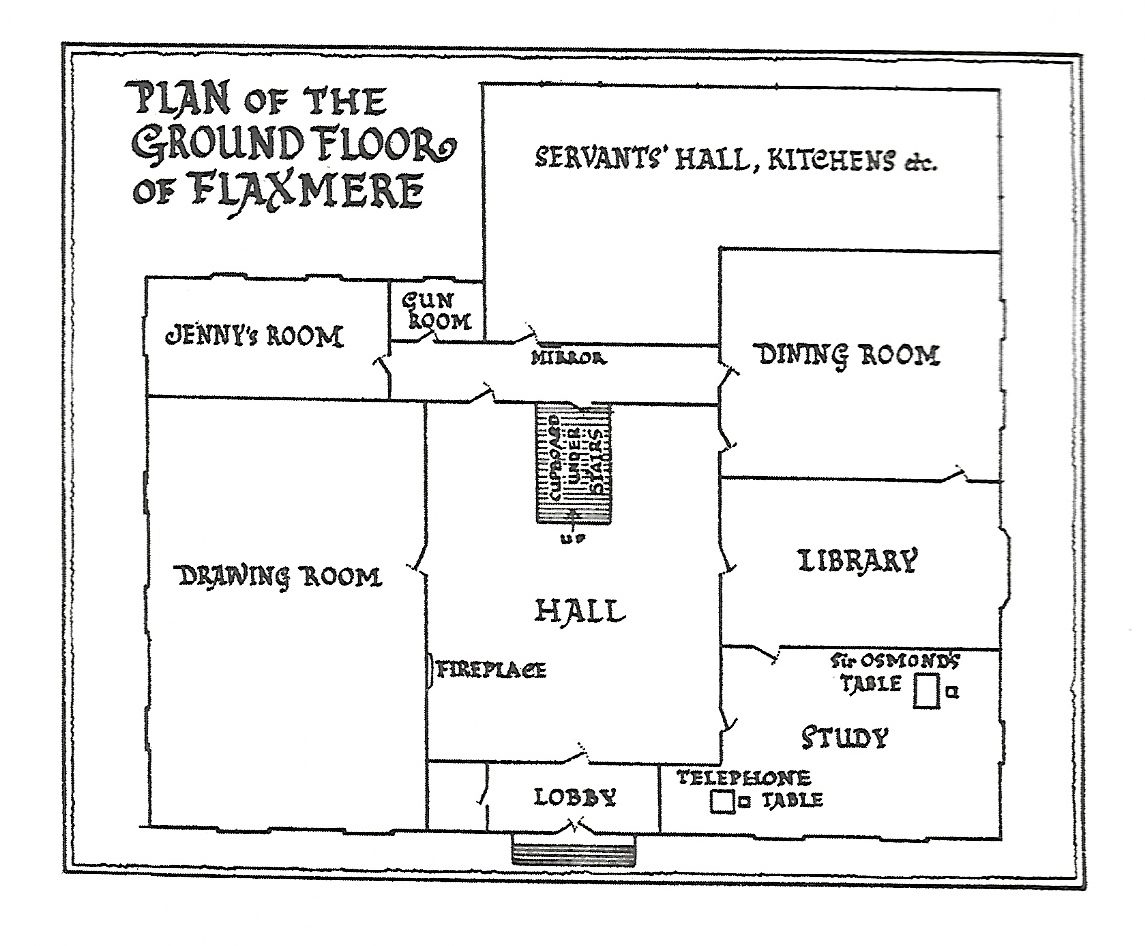

You talked about the role of maps and plans in detective novels – presumably they’re intended to encourage active engagement in puzzle solving?

Yes, I think that’s right. The thing about the plans is that they’re never terribly good. The one that I mention in the book The Santa Klaus Murder, which is one of those wonderful British Library ones that they suddenly rediscovered and reprinted, if you actually read the thing and look at that map, it doesn’t make any sense at all.

So why would that be? The illustrator presumably would have read the story?

Well, I’m not convinced of that. I think reading the story would have been very quickly done. And it may be that the writer hasn’t actually got the architecture right, in which case I suppose it makes the puzzle even more infuriating for the reader.

Would the writer have had a consultation with the illustrator?

I really don’t know. My sense is probably not, because many of the very popular ones were produced very quickly.

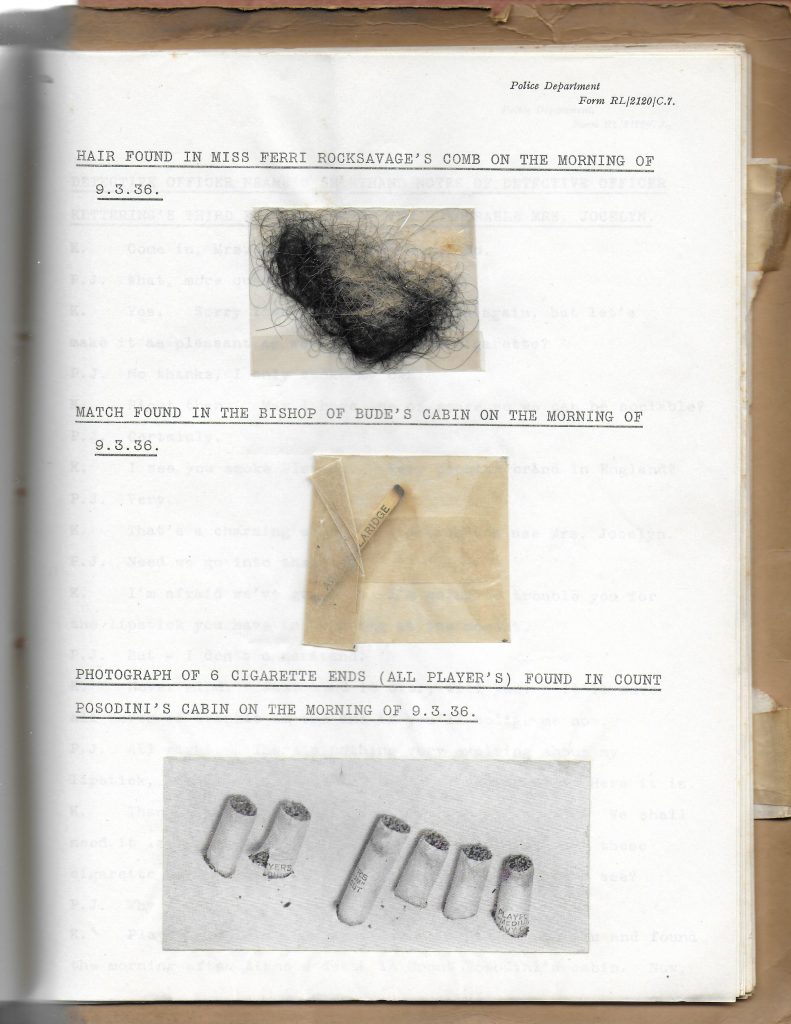

Can you tell us about that extraordinary dossier you describe in your book, which sounds more like a kit or a game, something a child would love, rather than a reading experience.

I do actually have that one, I bought it years and years ago, I just found it in this junk shop I used to go to. And it’s quite fascinating, it has things like a piece of hair, a cigarette stub, bits of bloodstained curtain. I think there was one more published but after that they died out because they must have been extraordinarily expensive to produce. Or they ran out of blood.

That really is reducing the detective novel to just a series of exhibits and clues which you then solve yourself, isn’t it, rather than engaging in a deeper way with narrative and character?

Yes, I think it’s very interesting. It was published in the mid 30s, when perhaps there was a wish to move further away from the Golden Age and offer something different. I’ve never found anything that is parallel to that. There are a few references about this one and the one more that was published, but after that it just vanishes.

Would costs have been a factor in stopping illustrations in fiction generally?

Yes, I think so. I think it’s cost, and taste as well, because presumably in the 20s and 30s people associated them either with magazine fiction, or earlier fiction by people like Dickens and Thackeray and all of the earlier writers.

However, it’s also an age of very fine illustrated books with wonderful illustrators, many of them women, who are producing illustrated versions of the classics, and contemporary fiction as well, in limited editions. And they’re appealing to a quite different readership, which is as much concerned with the book as with the fiction that is part of it.

But the other thing that is interesting is that magazine fiction is almost always illustrated. It’s a bit like the kind of paperback fiction that you find in the vaults of charity bookshops these days, they’re very often fairly strongly moral in tone, and they move towards a very satisfactory conclusion.

What I found was that the women’s magazines are actually much more precise and much better structured than most of the ones for men. Although the women’s magazines are very much centred on the home, and it’s all about cooking and flower arranging and various other things, once you get over the barrier of thinking that their lives are curtailed, if you like, just by being stuck at home all the time with the children, what’s going on in these magazines is showing how to survive that, and how to do it very well. There’s a strong element of nurture that is involved there.

For instance several of them have wonderful tiny cutouts, double page spreads which will give you sixteen tiny pages when they’re cut and folded. These would be special little magazines for children which come with the woman’s magazine. There’d also be knitting patterns which are for the children as well, and some of them actually give away dress patterns which are very complicated sheets of tissue paper that you’re supposed to pin on the fabric. There’s something very positive about that, and you realise that they’re performing a very important function. And also through the fact that you can write in with your own suggestions about how to hem a curtain, or whatever, that’s creating a community, and you realise that a lot of these women would have been very lonely. So it’s a very positive thing that they were doing, alongside this dual existence, that on the one hand some of the stories and some of the illustrations are very glamorous, but alongside that is the actuality of doing the washing and the cooking and all the rest of it.

I came to think of these magazines as very important survival mechanisms, keeping people together in families and especially in communities, because of finding a shared interest, because you realise that one of the problems with the great explosion of house ownership, which is really to do with building societies in the 20s and 30s, is that people are stuck in the home for much of the time. In the Victorian period that does happen to some extent, but it’s not quite as extreme as it is in the 20s and 30s with the growth of suburbia, and the fact that much of suburbia is subsidised by the railways, which means that the houses are built close to railways, so you have to have a job which you reach through the railway, which takes you away from that community, whereas in earlier periods you perhaps worked closer to where you lived. And that’s something I find very interesting, social change that nobody seemed to have thought would happen.

A lot of women must have felt quite lonely when they moved out into the suburbs where there‘s less of a community than terraced streets, perhaps, where there’s always someone close at hand to chat to and share things with.

Absolutely, yes. The very interesting thing about the development of, I think it was Harlow New Town, or one of the new towns, is that they quite deliberately had a small apartment at the end of each street, and that was intended for an an older couple, or an older woman, who would be there to advise the younger women with their children, which makes quite a lot of sense.

Because people are further from their own parents or family members who might have provided that support?

Yes, I think that’s certainly true, and increasingly so with the new towns, because by definition they’re new, and people are moving away from parents, and friends and family. From around about 1930/31 people who had a steady job were actually doing pretty well, the house prices were coming down, the prices of most things were coming down, so they could afford to move up a notch or two.

What I’m trying to say in relation to this reading business is that it’s another way of extending awareness and having a different world, which I think is very important in that period. In the chapter where I talk about house design and the number of books which actually show the designs of houses, you realise that this isn’t something that people are going to rush out and buy, it’s another kind of fantasy, it’s another way of furnishing the house in the imagination.

And I think that the novel, and particularly the crime novel, is very much within a part of that, because you have a clear aim, which is to find the villain so that life can go back to placid actuality, which of course never existed, and there’s a terrible, terrible irony about this, because of course In the 20s people are longing to go back to normality and peace, and in the 30s there is considerably less peace around really from about 1935 onwards. There’s this almost desperate plea to make things better and make things static, to have a resolution. This comes out in the way that houses are built, they almost all look the same, but there are tiny differences if you walk down one of these streets, in the way that they are painted or the quality of the windows and things like that, and I think the crime novel is one of the symptoms of that.

Stuart Sillars is Emeritus Professor of English, University of Bergen. He has written extensively on the exchange between words and images, including books on their relation in Shakespeare, the Victorians, and the two world wars.

#1920s #1930s #illustratedfiction #betweenthewars #womensmagazines #detectivefiction #crimefiction #magazinesforwomen #bookillustrations

A really interesting interview – I had no idea that Christie and Sayers started out with illustrated stories in magazines! Sounds like a fascinating line of research. I’ve just started reading a beautifully illustrated Folio Society edition of Wessex Tales, which is making me wish that I owned more volumes like it: the images definitely contribute something extra.

Thank you for this very stimulating interview. I was really interested in the way in which women’s magazines offered not only a sense of the status quo and community amidst uncertainty but also the fact that they provided creative opportunities in the midst of a workaday world. The connection between that and the desire of detective fiction to construct a sense of security and continuity fascinated me. How a tone and aspiration pervades a whole culture and the way we live, even to how we construct the very housing we reside (or hope to) reside in, made me think. Thank you.