David Henty is an extraordinarily gifted artist who paints copies of paintings by well known artists, such as Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Monet, Modigliani, Basquiat, Lowry, Rockwell, Sickert, Picasso and many more. Is this art forgery? Not really, because David is transparent about his paintings, signing them on the back and selling them openly as copies – there is no deceit involved.

Norman Rockwell’s Saying Grace by David Henty

Norman Rockwell’s Saying Grace by David Henty

David was already copying pictures from books when quite a young child. He remembers a book at home which had a reproduction of Hogarth’s Gin Lane, which he copied when he was around nine or ten years old. He never thought this was unusual, and admits he thought everybody could draw.

When adolescence hit David ‘like a cricket bat to the head’ he, by his own admission, went off the rails and found himself on the wrong side of the law for some years, resulting in a short stretch in prison for forgery. It was during his time in prison that he started to paint in earnest, and discovered an enduring passion for art, which led ultimately to a new direction in life and a legitimate career as an artist.

David’s paintings are commissioned by all kinds of organisations and individuals around the world, including film companies and television producers, interior designers and private investors. A David Henty copy has a distinct cachet, and sells for several thousand pounds. Some wealthy art investors, who can afford to own an original painting worth millions, like to buy a David Henty copy to hang on their wall, while securing the original in a vault.

Copying another artist’s work is technically extremely difficult, more difficult in some ways than painting a new work from scratch. To produce a copy that is well nigh indistinguishable from the original requires tremendous skill. David’s preparation involves in-depth research into the artist’s technique, their palette, brush strokes and pigments. But the preparation is not just technical, although that is of course essential, and of necessity meticulous and painstaking. The fact is that David cannot paint a copy of an artist’s work until he has achieved an intense, imaginative affinity with the artist’s psyche. This process involves extensive reading, prolonged viewing of the original painting (if accessible), watching documentaries, listening to radio programmes and podcasts, and so forth. He describes the “flow state” of mind he needs to enter before he can paint, a kind of trance-like immersion in the artist he is copying, which enables him to inhabit the imagination of the artist and consequently replicate their work. If he cannot reach this “flow state” with an artist, he cannot copy their work.

Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus by David Henty

Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus by David Henty

David is passionate about what he does, he is utterly obsessed with art. All he wants to do is paint, and when he can’t do that, all he wants to do is talk about art. Some might argue that copying devalues the original, but David’s remarkable paintings are a deeply-felt tribute to the artists he copies. They are works of art in their own right. However, there is no doubt that the art of copying raises all kinds of uncomfortable questions about the intrinsic value of a painting, as opposed to its market value. If art experts are hard pressed to distinguish a copy from an original, why is one of them worth millions while the other is not? Why does the (supposedly) authentic signature of an artist confer on that painting a vastly inflated market value, as opposed to its exact copy hanging beside it? Of course a prospective buyer wants to have confidence in a picture’s provenance, wants to feel that it comes with a patina of authentic history, touched by the artists’s creative genius. But is the physical picture itself intrinsically more valuable than the copy beside it, which looks exactly the same?

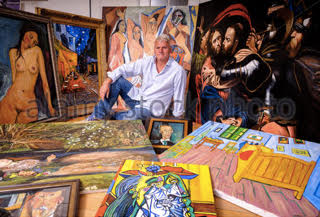

A room full of art

A room full of art

In the western cultural tradition copying is largely frowned upon as an affront to the original artist, or perhaps to a post-Romantic concept of the artist as an inspired individual of genius. In other words, if someone can replicate a Renoir, how can Renoir still be considered special? And yet despite this disapproval among some connoisseurs, experts, and art critics, there are evidently people happy to pay for a top quality copy by an artist like David Henty, who told me that people who buy his copies value them as an authentic piece of art, with the texture and physical presence of a painting, as opposed to a machine-generated print.

We can only wonder how many alleged originals hanging in galleries around the world may not be what they are claimed to be. And yet visitors to those galleries, blissfully unaware of that possibility, will stand in admiration before great paintings and experience their beauty and power regardless. As David repeatedly says in his book Art World Underworld: ‘people see what they want to see’.

Pictures provided by David Henty and Rosalind Esche

David Henty was born in Brighton in 1958. During a short stint in prison over 30 years ago for forgery, David discovered his passion for art. He has been painting copies of famous paintings by renowned artists, and creating his own renditions of ‘undiscovered works in the style of the artist’ ever since.

#davidhenty #artworldunderworld #artforgery #artcrime #brightonartists #crimefiction #crimewriters #brightonauthors #peterjames #roygraceseries #pictureyoudead

This is a fascinating article, covering the career of an interesting man and raising questions about the authenticity of art itself. I was particularly struck by the connection created between the ‘original’ painter and the artist ‘copying’ a painting during the creative process. I found the issue of identity in the artistic process and what part it plays thought provoking. I am currently reading the latest Peter James Grace novel and found the crossover between the ideas in this article and the narrative in ‘Picture You Dead’ illuminating. I haven’t finished the novel so I am yet to see how this crossover plays out. Thanks to Rosalind and David for this.

A really interesting piece. I can’t conceive of the ability required to be able to replicate the works of artists from so many different periods and styles! (I’d love to know which artists he is most passionate about, and who he finds particularly easy or difficult to reproduce.)

Thank you Rebecca, I’m glad you found the piece interesting. I hope your questions will be answered when David’s interview appears on our podcast Crime Scene – Crime Writers in Conversation, available shortly on Spotify, Amazon and Audible.

I suppose that art differs from other creative endeavours like writing and composing inasmuch as the finality of the artistic creation is an artwork, an object, which can, with learning and skill, be copied, whereas one can strive creatively and technically to write like Chekhov, for instance, or to compose in the style of Beethoven, but simply copying out a short story or string quartet would involve no creative or technical striving at all.

Plus, one pays money for an artwork, be it by Rockwell or David Henty, whereas one can own an original manuscript or score, but not the story or the music. Traditionally, aspiring artists have learned from great masters as apprentices in their studios or by copying their works in galleries. Where is the dividing line between an artist’s original conception and execution and another artist’s copying or hat doffing? And where will artificial intelligence take us?

Thank you for a very interesting piece.