I thought we could start with your police career, Graham. Could you tell me why you wanted to join the police?

All I ever wanted to do was join the police, my uncle was in the old Brighton Borough Police and it came from him really. He used to come round to our house, he was traffic police, and he used to go dashing off when the radio went out, it was exciting so it just kind of grew from there, and my dad was a volunteer police officer. There was never a plan B really, and I think that worried my parents because you know, same with any job, you’re not necessarily going to get the first job you go for. I said to them, “Well, if I don’t get into Sussex Police, there’s 42 other forces that I can try and I will”. And I was lucky, I got into Sussex.

It sounds a bit clichéd, but I just wanted to work where I could help people, where I could make a difference. I didn’t fancy the idea of being in an office, although that’s obviously where I ended up when I got more senior. So, it was a worthwhile career to embark on, I was only 18 so I had no life experience at all and that was a bit of a challenge, but I soon learnt it!

So you learned on the job and went on training courses as well?

So locally our initial training was at Ashford in Kent, that was the regional training centre. So we went there for 10 weeks’ residential, home at weekends, then you come back to your force, do a couple of weeks just understanding the local procedures and then you’re on to your police division. I was at Bognor Regis first of all, 18 and a half, wet behind the ears, out with a tutor constable. I wasn’t allowed out on my own until I was 19, so I had a very long tutorship.

That’s young! You could come up against anything.

Well, that’s right, but you do have to learn on your feet really. You go on courses throughout your probation and throughout your whole career, but you do have to learn from how you do things. I was no size, I was very young and I was often walking the streets on Saturday night in Bognor, knowing that my backup was quite some way away, and I knew straightaway that I was never going to fight my way out of any situation, so I had to develop a kind of gift of the gab, and just learn to use humour and very fast lips to get myself out of trouble!

And did that work?

Yeah it did, I never got assaulted in those days. In fact it wasn’t until two years later when I came down to Brighton that I actually got assaulted and that wasn’t that serious. I got abuse, people used to chant “Does your mum know you’re out?” and things like that as I was walking down the street, but I kind of laughed it off, I couldn’t do anything else really. There was no point in me turning around and facing off a gang of 25 year olds, so I’d just laugh it off and say “well, I’ll phone her when I get to the next phone box and let her know”!

Did you ever feel anxious or were you quite confident?

I did have anxiety at times. I think you’d be a bit strange if you were going into a violent situation, or a shop’s been broken into and you’re going in to try and see if anyone’s still in there, if you didn’t feel a little bit of fear, but you just have to go through that, really, you have to work through that. I remember my tutor constable saying to me that “people call the police ’cause there’s no one else left to call. So if we don’t do it who else is going to?” So you’ve got to step up, and that was how I ran my career and how I taught other officers as well as I went through.

I’ve read that you went up through every rank during your career.

I was every rank in Brighton and Hove. So Brighton and Hove has officers from police constable to chief superintendent, and most people that arrived at the chief superintendent rank hadn’t fulfilled every rank in Brighton and Hove. I sort of darted in and out occasionally, but I served every rank in Brighton and Hove in some capacity.

What was your favourite rank? What did you enjoy doing most?

I think enjoyment-wise probably detective sergeant, that’s a great rank because you’ve got just enough seniority, it’s the second tier, so you’ve got enough seniority to pick and choose a little bit of what you’re going to do, but also you’re low enough down the ranks to actually go out and do it. Once you get to inspector, certainly chief inspector, you’re more or less office bound. It’s not all admin, but you’re running big investigations, I describe it as you’re like a project manager, really, particularly if you’re a Senior Investigating Officer on a murder, you’re project managing so many strands to investigate that murder you don’t get out, but detective sergeant was a great job, I loved it. And I worked with some brilliant people in Brighton and Hove at that rank.

So you don’t get out at all once you reach a certain level, or can you? This comes up in Peter James’s Roy Grace books doesn’t it, that Grace still likes to get out and be in the thick of it.

Yes, and detective superintendents don’t normally go out, but it’s within their gift to go out if they want some fresh air or they want a bit of excitement, and Peter’s built his whole series on the fact that Grace does that. In my book, Bad for Good, Jo Howe does that once or twice, which is kind of the norm really. But you don’t get out very often, but the pressures and the variety come in different forms. So if there was a massive protest closing down Brighton and Hove, or a dynamic firearms incident or something like that, I’d probably be in charge of that, but from the police station, because that’s the best place for me to command from.

Some people prefer to stay in response their whole career, don’t they, because they like the variety and the excitement?

Yes, and it’s a very noble ambition to do that, you know. A lot of people say to me “they’ve been a constable for 20 years, they can’t be very good” but it’s quite the contrary, it’s because they are very good at it, and they enjoy it, and they could be role models for people coming through. We had an officer here in Brighton, she joined I think slightly before me, and she did 30 years 24/7 response and never did anything else. And in the end we put her up for a Queen’s Police Medal, and she was in the honours list one year because of her dedication to frontline response. She was a role model, particularly for women coming through, dealing with all of the pressures there were particularly around in the ’80s and ’90s, she was great for that.

Can you think of some of the major changes you experienced in your career, good and bad?

The forensics have just changed beyond all recognition. DNA hadn’t even been discovered as an investigative tool when I joined the police in ‘83, you had fingerprints and blood grouping and that was it really, so that was huge. And technology in surveillance, surveillance used to be sticking people behind somebody and following them around. There’s a bit of that now, but most of it is technical because of phones, CCTV, all kinds of data sources, you’ve got telematics in your car, all those sorts of things. So technology has made things not easier so much, but certainly it’s given greater opportunities to be able to catch people.

I think the negatives – I could talk about the police numbers and the cuts – but I think there is a lack of respect for the police now, and it’s not just the police that suffer. I think some people seem to think that because they know a little bit about a profession, be that being a police officer, a journalist, a politician, that they’re entitled to portray that they know everything, so criticism comes much quicker. There’s not much empathy for the police nowadays. I was talking to somebody the other day, who was making quite a difficult arrest in a shopping centre and they managed to get the chap restrained in the end, and he said that he was just surrounded by people on their phones taking video of it, no one coming to help. I certainly remember in my young days, not just me because I looked like a kid, but with other people as well, you’d quite often get members of the public coming in and just helping you hold someone while you got the handcuffs on.

Why do you think that is? Is this a general sort of malaise about authority, or is it because of high profile cases in the media about the Met?

Yes, I think there’s a lot of that. I think people have lost a lot of respect for the police because of some of the dreadful things that individual officers have done, and in some cases, cultures within particular forces. So there’s not that unconditional respect that there used to be. But the way these things are reported leads people to believe that that is the norm, and I genuinely don’t think it’s like that.

People do talk as if the whole of the police force is bad in some way because of individuals like those at Charing Cross. But there are thousands of police officers, clearly they’re not all going to be like that.

No, they’re not. When I was here in Brighton and Hove I had about six hundred officers on my division and I think about three or four hundred civilians, and I was proud of every single one of them, I really was. And the odd one or two that erred, I remember people coming to us, to myself as commander (it’s a big thing to come to me, even though I’m quite a warm and friendly person, I hope!) and they would make a complaint about a fellow officer who they thought had used excessive force, or who was cheating the system in some way. Police officers despise officers that are corrupt or violent, or bullies, as much as the public do, and will do everything to root them out.

It’s a shame then, isn’t it, that this is the public image of the police at the moment? What do you think can be done about it?

I think it’s down to policing to show that it’s not that, and actually in the main it never was that. Everybody joins the police at least to do good, to be fair and to be equitable and to treat people well. Some people veer from that at some stage, but very few. So it’s up to the police, I think, to show that they’ve changed, and certainly some of the things that are going on in London at the moment, you have to question how long that can take, how long those opinions will take to change and how much proof needs to happen. I think it’s seismic.

I heard the Secret Barrister say on his radio broadcast that all the police he’d ever met and worked with were decent, good people trying to do their best in a difficult job.

I’d agree with that. I’ve met some incompetent police officers in my time, and I’ve met one or two that have let themselves down because they’ve been lazy or distracted and therefore dropped the ball. I’ve met one or two who were violent, but they’ve all been dealt with. I mean they’re found out quite quickly, but by their peers, not by people like me, their peers will find them out, because with the majority, the overwhelming culture in the police is hard work, courage and standing in between good and evil.

People must be reluctant though to grass up their colleagues, aren’t they? The police is quite a family, quite a cohesive culture.

You’d think that but my experience is no, they’re not, they’re not reluctant at all. There is this kind of myth that professional standards departments are hated because they chase down corrupt officers. You know that there’s nothing officers detest more than somebody that is corrupt or lazy or uses too much force or whatever.

Because it gives everyone a bad name, doesn’t it?

It does, yes. I’ve been on the streets when there’ve been scandals elsewhere in the force and it comes straight back to you, you know “you’re all the same”. I know that when Wayne Cousins was identified as being Sarah Everard’s killer police officers were getting vilified on the streets, and actually the judge in that trial said that it was one of the most thorough and tenacious investigations (I can’t remember if those were the exact words) that he’d ever seen. And it was the Met that caught him, the Met caught one of their own.

And yet people talk about it as if that’s a cultural norm, but the reason it’s such a shock is that it isn’t the norm, surely?

No, it definitely isn’t the norm. There were some stupid people that don’t deserve to be in the organisation who got involved in WhatsApp chats around it, and there are police officers in prison now for taking photos of dead bodies and sharing them. That is stupid, it’s criminal and it can’t be tolerated. But you know, I’ve never met anyone who’s done that. I’ve never met anyone who’s met anyone who’s done that. It is rare.

Has the culture changed a lot since you were in the police, or are you saying it didn’t really need to change that much?

No, no, I think it has changed in a lot of ways. I think in the early ’80s, certainly the force was a lot less tolerant of diversity at that time. I can almost picture now every woman officer that was at Bognor, I can’t picture every man officer, but there were so few women I can picture them now nearly 40 years on. We had no officers of colour there at all, none, no out gay officers, be they male or female, certainly no transgender or gender neutral people at all that were out, so that was really, really tricky for people that were part of those demographics. Until the Police and Criminal Evidence Act came in in 1986 the police was less accountable, so what went on in interview rooms wasn’t really seen too much. But I served three years in that pre-period and I didn’t see anyone being beaten up or thrown in a cell for days or anything like that. It must have happened because that’s one of the reasons why the Act came in, but it wasn’t prolific, certainly in my experience it wasn’t prolific.

What do you say to people on the street ,after some awful case, who say you are all the same?

Well, if they are prepared to hang around and have a conversation with you, which often they’re not, then I would try and speak to them and say “look, do you really think that we aren’t as repulsed as you are by this, do you really think that we support those officers, do you really think that this is something that the police service wants within its ranks?” But whether they listen or not, quite often in this day and age people are very quick to make their minds up and not change them.

There’s been a lot of noise in the media about how people are screened to get into the police after the Sarah Everard case and those awful incidents at Charing Cross. Is there a problem with screening, or is it just that now and then someone will go bad?

I don’t think there’s a huge issue with the vetting of people coming into the service. Only 5% of people that apply actually get in, it’s very few, 5% that start the application, because there are various kinds of trapdoors throughout it, and the first one is around your values and beliefs. It’s multi choice questions around values and beliefs, and you can’t hide in those ones, they’re not obvious.

You couldn’t lie your way through them and convince everybody?

You get about 60 questions and the algorithm would find you out. Then those that do get in, a proportion of those don’t get through their first two years, not a huge proportion because the police want to keep them. But I think there’s a lot of that at that early end, a lot of vetting and a lot of scrutiny for the first two years, and I think the cultures that we see reported in places like Charing Cross, develop over a long period of time. It’s having the systems and the abilities, and the right people to be able to spot when things are starting to get out of hand, and that’s a leadership issue, there’s no question about that. That’s down to sergeants, inspectors, everybody of rank, plus experienced constables, to go “hang on a minute, we don’t talk like that here, that’s not how we behave here.” And that takes courage and it also takes support. So if you’ve got a sergeant who’s brave enough to do that, yet their inspector is out drinking with the lads later on that day, it leaves you a bit vulnerable.

What’s your attitude to graduate entrance? Do you think it’s a good thing to have different routes into the police?

Yes, definitely a good idea to have different routes in. I think the police recruited from the same pool before, you know ex-military and kids really when I joined, and obviously I fell into the latter.

I’m not a big fan of people having to be graduates to come in, or even having to do a degree to get through their probation, which is what they have to do at the moment, because some people just aren’t suited to academic study. I’ve worked with some incredible people that really struggled to get through even their basic probationary courses. I was at Bognor, as I said, and down there you had people who were at the Royal Military Police barracks in Chichester, a lot of people out of the navy in Portsmouth, a lot of them lived in the Chichester area and around there, and they joined the police and worked with me in Bognor. They were fabulous police officers but not academic in any way, so I think you need a mix.

I’m not a big fan of direct entry at senior rank. I think that is something which is going to cause some big issues going forward.

How does that work?

Well, you can join as a superintendent, or you can join as an inspector, with no background in policing. The people that I’ve met who’ve gone in that route are lovely people, clever people, they’re bright and they bring a different perspective, but my worry is, when I was in senior command roles, I would sit there sometimes – it can be quite a lonely place to be – drawing on every ounce of my 30 years’ experience that went before, knowing what it’s like.

If you’ve got a group of six officers trying to stop a mob invading Brighton Town Hall because they want to disrupt the council meeting, I’ve been there, I know what that feels like, so I know the impact of the decisions that I’m making at a strategic level, and how that’s going to affect the people that are actually standing there taking the bricks. So I’m not a big fan, but what I am a big fan of is very early talent spotting. Let’s start to identify the bright and the best as they come in and accelerate them through the system, expose them to all of the experiences and the challenges that they’re going to need when they are operating at that high level. But not just parachute them in, I just worry about the officers themselves, and I worry about the public in those situations.

How long has it been the case that people with no policing experience whatsoever can enter at high level ranks?

About eight years, it was just after I left that that came in. I was very vocal on local radio about that, which is interesting, because the then Chief Constable Giles York was very vocal in favour of it, and he’s actually a friend of mine, so we agreed to differ on that!

Do you have any feelings about the criminal justice system being broken, as people say, and about the prison system? I’m thinking of Bob Heaton in your book, who is so shocked at what he sees in prison that he doesn’t want to work for the police anymore.

That’s right, he decides that he’s not going to subject people to these bullies, and some of the bullies aren’t always on the wrong side of the door. I think the theoretical model of our criminal justice system is very good in terms of the onus is on the prosecution to prove beyond doubt that the defendant is guilty. There are some obligations on the defence to flag up what their defence is likely to be, and there’s disclosure obligations both ways. I think the bureaucracy of it designs in justice denied for people. I think particularly now when you’ve got such a backlog because of Covid, that you’re not going to get somebody to trial for a year at least.

That’s terrible.

It is terrible. And in a lot of those cases you’ve got innocent people on remand in prison who may be acquitted. And if they are acquitted, they’ll just be told “you’re free to go” and there’s no comeback for them.

I think prison is a good place to protect the public, so putting violent people in there, putting sexual offenders in there, because I think the public do need protection. I think as a mode of punishment and rehabilitation it just doesn’t work. When you look at people who are imprisoned for non violent offences, for offences against justice in some cases, for contempt of court or something like that, I’m not saying they shouldn’t be punished, but is that really a place for somebody like that, for fraudsters, white collar criminals? You put them in prison for five years, what’s that actually doing? The way to hurt fraudsters is to go after their money, go after their assets, that’s what’s really going to hurt them. It’s just a very expensive kind of warehouse, really, and more often than not people that go in come out worse.

And we have more, don’t we, in prison than most countries in Europe?

Certainly in Europe I believe, yes, but we tend to use it with impunity and for no good reason.

So you’re fairly jaded about any rehabilitation that could take place in prisons, you don’t believe it works?

No, I don’t think it works. I think you have to have quite a long sentence to even get on the first rung of rehabilitation in prison. Short sentences don’t work. If you’re a drug addict and you commit a theft or robbery, and you get six months, you’re getting no rehabilitation in there. You’re probably going to get your hands on more drugs in there than you could out, and you’re going to come out without a job, without a home, without money, possibly without a family and with a raging drug habit, and there’s one place you’re going and that’s back again, and it’s just crazy. I get very agitated about it!

And they just get shoved out the door, and that’s it, there’s no support at all?

Well, they have probation. If they’ve been sentenced to a year they come out on licence, but under a year they come out at the halfway point and they get post-sentence supervision. It’s not on licence, it’s basically keeping an eye on them, they don’t really do anything much other than to make sure they’re not offending and they’re living where they’re supposed to live, they can’t, they’re as underfunded as everybody else.

How can drugs be so prevalent in prison?

Well, there are so many ways of getting drugs in. Prison officers themselves will tell you, despite they have these chairs that visitors sit on that they’re supposed to X-ray and find drugs or phones or whatever, it even gets in there. There’s talk of prison officers bringing it in. There’s spice, which is synthetic cannabis, can be liquefied and then what happens sometimes is that somebody will make a kid’s drawing and send it in, as if “oh look, your little boy’s done you a nice painting” and actually the paint is infused with spice. Some prisons photocopy those or anything that comes in like that, they just photocopy it and give the inmate the photocopy. They’re so imaginative! The one thing that prisoners have got is time to think.

And what about corruption? Do you think that’s not as rife as TV dramas like to portray?

I don’t think it is as rife. I mean there is corruption as there is in local government, national government, because it’s human beings, but my experience is that corruption is on an individual basis rather than on an endemic basis. There have been examples of big squads that have been held corrupt in the ‘70s and ‘80s, but I think it’s more the individual, and certainly the corrupt officers that I know of that have been dismissed and sent to prison have been working very much on their own, and it’s been, I say low level, no corruption is low level, but no one is buying big manor houses in the country or driving Rolls Royces, it’s almost, well, it is quite pathetic really. The worst kind of corruption is mishandling of evidence and fitting people up, and there’s quite a lot of safeguards around that now, but that’s always a worry for me, the innocent going to prison.

What’s the most memorable case you worked on?

I worked on the Russell Bishop case, which I’ve written about [in Babes in the Wood], but another one which always stuck with me was, and I wrote about this in Death Comes Knocking, a chap who ran a pizza shop in Hove, he ran it with his partner, they were a lovely couple, really unassuming. After locking up one night, as they got home she got out the car to go and unlock the door and he parked the car and then he got jumped and then taken away in his car by two people and beaten almost to death, left blind, very nearly died and that was all for a couple of hundred quid. They wanted his safe keys so they went back to the shop and emptied the safe, but didn’t know he’d done the banking on the Friday instead of the Monday, so there was hardly any money in there.

I actually met him, I went to see him when I was writing Death Comes Knocking, they were still living in the same flat, still together, just an amazing sense of humour and humility and just getting on with life.

I remember when we were sitting in court, there’s a process called “warrant of further detention” – when you want to keep people in custody longer than 36 hours, you have to go to court and a magistrate has to grant that, so we were behind the prosecutor and we had old style Nokia phones in those days, and I was literally waiting for somebody to text me to say he’d died, and that we were changing the investigation to a murder, so I could brief the prosecutor, but he didn’t die, thank goodness. One of the people who did it had no previous convictions at all, and the other one only had a couple for burglary. It stuck with me for a long time.

Yes, I got that impression, I read your books and also watched that documentary Peter James did about the “Babes in the Wood” case – so many police officers say how things haunt them for their whole lives, that they never forget certain crimes.

Yes, certainly the “Babes in the Wood” one lives with everybody who was involved in that, which was interesting when I wrote the book with Peter, because I couldn’t speak to everybody, and so many people wrote to me afterwards saying “you should’ve spoken to me, I was the scene guard here, I’d’ve had something to tell you.” You know, everyone’s got a story about it, and sometimes you just have to go “yeah, but I only had ninety odd thousand words, that’s all I had to tell the story” – it could’ve gone on for ever otherwise!

Did you ever get jaded and cynical? Do you think it’s inevitable after years and years in the police seeing the worst of human nature?

I don’t think I got jaded, I think not much surprised me after a while. Some of the things people do, or the lengths they go to to scam each other or hurt each other, not a lot really surprised me. I’m not saying I’ve heard it all before, but it’s just like “Oh, that’s what they’re doing now, is it?” So you do get a bit like that.

But certainly the way I was trained, and tutored and brought up really, was that you always try to put the victim and the family at the centre of everything, so you know you can’t afford to be dismissive about anything, even where you know it was bad on bad crime, you know, where somebody attacks a rival criminal or something like that, at the end of the day, they’re still someone’s son, daughter, brother, partner, whatever, and you try and think about the impact on the family as much as you do on the individual.

You’re seeing the worst of human nature most of the time, aren’t you? It must be quite hard to keep all of that in mind, but the families aren’t responsible, are they?

No, though sometimes the families are problematic as well, but they still hurt. If you’ve got to go tell someone that their son or daughter has been murdered or died in a horrific car crash by someone driving in a ridiculous manner, however much they might hate the police and been on the wrong side of the law they still cry, and they still want you not to be telling them that, they’ll still live with that moment. Sometimes I dwell on it, sometimes I think of all the death messages I’ve given, and I know that every one of those people will always remember me knocking on the door and what I told them. They’ll never forget that police officer’s knock, whether they be holier than thou or somebody who spent half their life in prison, they will cry, they will hurt.

Did you dread doing that? Was that one of the worst things you had to do?

Yes, it was horrible. You walk up to somebody’s house and sometimes you’d see them like a silhouette behind a curtain, or moving around, or the curtain might be open and you see them watching the telly or having a cup of tea or a drink or something, and you think “I’m just about to devastate your life and you don’t know that yet. You’re sitting there, life is rosy, and I’m just about to crush you with what I’m going to have to tell you.”

And reactions could vary hugely. I’ve been attacked for giving that message before. They’re not attacking me, they don’t want me to say what I’m saying, they don’t want to believe it, so you don’t take it personally or anything like that, but I’ve been attacked. And sometimes I sat there for hours and hours and hours ’cause they’ve not wanted me to go, and I’ve not felt that I could go. Sometimes you think is that professional, to just keep staying there? I just think that I’d owe it to someone. I never got criticised for it, but you know that while you’re sitting there you’re not answering the other jobs that are coming over the radio. But I think you’ve just got to do what you’re doing the best way that you can.

I remember my old boss here Malcolm Bacon, a detective inspector, dealt with a child death, and the police and the prosecution couldn’t prove whether it was the mum or the dad that did it. One of them did it, one of them was guilty of murder and one of them wasn’t guilty of murder, but might be guilty of lots of other things, so they both got acquitted because you’ve got to prove it beyond reasonable doubt against each one. And he got the law changed, he just made it his life’s ambition to lobby government and to get the law changed. We were very lucky because Lord Bassam, who was one of the Home Office ministers, was ex-leader of the Brighton Council, so Malcolm used him to start this debate going and they created an offence of Causing or Allowing the Death of a Child, which carries a significant custodial sentence, so cases where both parents don’t say anything, people are being convicted of that now, and that’s all down to Malcolm Bacon. That came out of one case where he just felt this huge injustice for this child that had died, and made it his life’s ambition to stop that from happening again.

Have you ever had a case where you knew someone was guilty and they got off and it was terribly frustrating?

The obvious one is Russell Bishop, that’s the obvious one. I’ve had serious assaults and burglaries, where people have got off and you just have to brush yourself down, really. It’s quite hard to adopt the mindset that your job is to get it to court. There are so many checks and balances before you get it to court. The CPS [Crown Prosecution Service] have to approve the charge first of all, and then they have to continually review it so that they’re satisfied there’s sufficient evidence. If it gets to trial the judge has to agree that there’s sufficient evidence for it to continue. When the prosecution case is finished, if the defence ask them, the judge can determine whether or not there is a case to answer, whether the prosecution has done enough. So if you get to the point where the jury are walking back in, you’ve actually done all you can, there’s nothing really more to do, so you can’t dwell on it. But it does hurt, again for the victims, it does hurt, and particularly when you’re trying to explain to the victims that it’s not about belief, particularly if it’s a personal crime like a rape or something like that, it’s not that the jury didn’t believe you, it’s just that they couldn’t be sure, and it’s only that element of doubt, because not guilty doesn’t mean innocent. In Scotland they have not proven, which is our equivalent of not guilty. If you’re found innocent in Scotland you’re innocent, here not guilty is not innocent. You hear people on the court steps sometimes claiming “I’ve been found innocent by the jury” – well you haven’t, you’ve been found not guilty.

That’s a really interesting distinction, which I think most of us don’t understand.

Yes, the standard of proof is mountainous, and if you don’t reach the summit of not guilty it doesn’t mean you’re not a climber, doesn’t mean you’re not brilliant, but you’ve only got to have the defence be able to sow a seed of doubt in the jury’s mind. And sometimes if the judge is insisting on a unanimous verdict, then the defence has only got to seed that in one of the juror’s minds and you’ll at best get a hung jury.

Going back to the Bishop case, it’s interesting that eventually, because of improvements and progress in forensics, he was finally found guilty years later.

Yeah, that’s right. The law changed first, that’s the first thing, which meant that in serious cases, like murder and rape and robbery and kidnap, if there was significant new evidence the Court of Appeal could quash the acquittal and order a retrial. That’s only been in place since 2005, so that happened. Science then caught up and meant that the minute forensic samples that were gathered in 1986 were re-examined. It was DNA within the tapings. So they taped Karen’s skin, they’re looking for fibres and hair and stuff like that, but in doing that (they don’t realise it because it’s 1986) they’re also taping skin particles off there, and in those skin particles was Russell Bishop’s DNA, and the first part of the prosecution case was to prove that there’s no way that Russell Bishop had any opportunity to touch Karen Hadaway’s naked arm legally. He’d seen her during the course of the day, when she’d been wearing a jumper, didn’t touch her, was stood away from her, so there was no way other than during the murder that his DNA could have ended up on her skin. That trial was in 2018 and I think that evidence came through in 2015/2016 so a long, long time after the murders.

Prior to that, there’d been a problem with a window of time for the murders, hadn’t there?

Yes, that was the prosecution’s fault really. Nowadays the prosecution don’t really tie themselves down to times unless they can be certain. But it used to be the convention that everyone wanted the time of death, they’d go to the pathologist and pathologists were more inclined in those days to bow to that pressure, so “oh yeah, you know, between 6.30 and 7.00” but nowadays you ask a pathologist the time of death, and they’ll say, “well, it’s between the time they were last seen and when they were found dead”. That’s how they frame it.

So that was nothing to do with the police and their evidence, was it?

No, no, in fact police had gathered evidence which discounted that time of death, because they had a witness who knew the girls who was waving to them at quarter to seven.

So why wasn’t that taken more into account then?

Well that’s something that we ask in the book, why? Because you’re backing yourselves into a corner and the prosecution counsel did that, with the CPS. As far as I’m aware, and I’ve spoken to the senior investigating officers, no one picked up on it until it was too late. A lot of people criticised the judge in that case, and I think there are some questions about the judge, but at the end of the day, the judge has to direct the jury based on the case that the prosecution presents, and the prosecution presented the case that the girls were dead by 6.30, so the judge can only present that to the jury because that’s what the prosecution case is, notwithstanding that there was somebody who saw them at quarter to seven.

So the police provide all their evidence and hand it over to the prosecution?

Yes, they work with the police, but at the end of the day, the barrister, the leading counsel, will decide how he or she is going to conduct the case, and that’s how they decided to do it.

To be continued …

GRAHAM BARTLETT was a police officer for thirty years and is now a bestselling writer. He rose to become chief superintendent of the Brighton and Hove force as well as its police commander. He entered the Sunday Times Top Ten with his first non-fiction book, Death Comes Knocking – Policing Roy Grace’s Brighton in 2016. He followed that up in 2020 with another non-fiction book, Babes in the Wood, the harrowing 32-year fight to bring a double child killer to justice. Both these books he co-wrote with international best seller, Peter James.

As well as writing, Bartlett is a police procedural and crime advisor helping scores of authors and TV writers (including Mark Billingham, Elly Griffiths, Anthony Horowitz, Ruth Ware, Claire McGowan and Dorothy Koomson) achieve authenticity in their drama.

#crimefiction #crimewriters #detectivefiction #brightonauthors #grahambartlett #policeprocedural

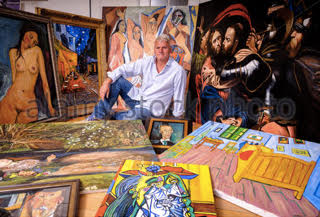

Norman Rockwell’s Saying Grace by David Henty

Norman Rockwell’s Saying Grace by David Henty Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus by David Henty

Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus by David Henty A room full of art

A room full of art

A couple of months ago I read the interview with Elly Griffiths on this blog and was inspired to buy one of her books. I thought I would start with the Brighton series and intended to buy the first book but (owing to not paying attention or being an idiot) I bought the most recent by mistake – Now You See Them. I read it at once and spent quite a long time thinking “there’s a surprising amount of backstory here for the first book in a series” before I twigged! At least I proved that there’s no actual need to read Elly Griffiths in the right order as the book was extremely enjoyable as a stand alone although I’m now going back to start at the beginning properly. I liked the Brighton setting and particularly the sense of time with the Mods and Rockers battling on the sea front. The pervasive presence of stage magic was also rather nostalgic for me – I’m of the generation that grew up with the Paul Daniels magic show being ubiquitous on TV and I imagined the character Ruby’s hit programme as being along those lines.

A couple of months ago I read the interview with Elly Griffiths on this blog and was inspired to buy one of her books. I thought I would start with the Brighton series and intended to buy the first book but (owing to not paying attention or being an idiot) I bought the most recent by mistake – Now You See Them. I read it at once and spent quite a long time thinking “there’s a surprising amount of backstory here for the first book in a series” before I twigged! At least I proved that there’s no actual need to read Elly Griffiths in the right order as the book was extremely enjoyable as a stand alone although I’m now going back to start at the beginning properly. I liked the Brighton setting and particularly the sense of time with the Mods and Rockers battling on the sea front. The pervasive presence of stage magic was also rather nostalgic for me – I’m of the generation that grew up with the Paul Daniels magic show being ubiquitous on TV and I imagined the character Ruby’s hit programme as being along those lines.