You write under the names Domenica de Rosa and Elly Griffiths – do you find that writing under two different identities affects your style?

I suppose I do feel like that a little bit. I was first published as Domenica de Rosa, which is my real name (my father was Italian). I wrote what you might call women’s fiction under that name. I think Summer School is my favourite of all my books.

The summer school of the title is a creative writing course in Tuscany – did you ever do a writing course like that?

No, I didn’t. I remember I got an advertisement to go on a creative writing course and I couldn’t afford it at all. It was in Tuscany, and I’m half Italian, so obviously I love Italy, and I thought it sounded great. I got the programme and the programme was “Morning: Stretch” which went on for an hour, and then “write” and then “go and look round a vineyard” and I thought this is lovely, I’d love to do that, but I couldn’t afford it. So the next best thing to do was to write about it. So I write all the pieces the creative writers do on the course, I write a little bit of each of their books, that was so much fun to do. But I’ve still never been on a creative writing course like that. I’d never taught creative writing then, but of course now I do teach creative writing at Madingley Hall in Cambridge and West Dean College in Sussex.

Then when I wrote a crime novel, my agent said I needed a crime name, partly because Domenica de Rosa is too lovely for crime. I guess it sounds like a romantic fiction name, but more than that it sounds made up, which is ironical really because it’s my real name. I remember at work I’d pick up the phone and say “Domenica De Rosa” and people just thought I was singing! The thinking was that crime was a new genre for me and it gave me a new debut in a way. My grandmother’s name was Ellen Griffiths, I didn’t really know her very much, she died when I was five, but the thing I’d heard about her was that she was a very clever woman, very literate, loved books but had to leave school at 13 and go into service, so I thought she’d really like her name on a book. I wanted to be Ellen, but when the first Ruth book came out, somehow I became Elly, and I remember asking my editor about it and she said “Oh, it just looked a bit tidier.”

I think my writing style is still my style when I write the Ruth books and the historical fiction series, the Brighton Mysteries. I think my writing is the same, but people often write to me saying they wouldn’t have known it was the same person writing, it’s so different.

How interesting, because I do feel that the Brighton Mysteries have a very different atmosphere.

That’s interesting. The Brighton Mysteries are seen as a bit sort of Golden Age – it says on the cover “recalls Agatha Christie” because Agatha Christie was quite dark, and I think there is a dark atmosphere to them, so I think you’re absolutely right about that, particularly the new one, The Midnight Hour, which has just come out. I went for a dark feeling, although hopefully there are funny bits as well. So I think you’re probably right, having said I thought that the style was the same, I think possibly those are a bit darker.

Do you think it’s because they’re set in the early ’50s at the start of the series, when there’s still rationing and there are references to people’s war experiences, so they have a more sombre atmosphere?

Yes, I do. And although The Midnight Hour is set in the 1960s, I suppose I wanted to show that the ’60s weren’t all swinging, that there was a darkness there. William Shaw, who writes brilliantly about the ’60s in his Breen and Tozer books, says for most people the ’60s didn’t start till 1970, and that’s true in a way. It’s partly about women’s liberation (one of the characters has been reading The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan) and that’s kind of central to the plot, making points like women police officers couldn’t drive police cars until the ’70s, that sort of thing, but there’s still a bit of humour in the books, for example the women are still always asked to make the tea.

So the female characters in The Midnight Hour are struggling with the restrictions of the times?

Yes, exactly. Emma, is married to the love of her life and has a very happy marriage, Edgar is a really nice man and he’s a modern man, and there were those sort of men in the ’50s and ’60s, but even so she finds her life restricting and frustrating and she wants to be working, and I really do sympathise with that. And I want to show the sometimes not such nice things she thinks, because we all think like that sometimes. She wants to support Meg as a young police officer, but also she’s a bit jealous of her because she’s a single woman and she’s out there, solving crime. I wanted to show that it’s all very complicated.

When I had my twins 23 years ago I was working at Harper Collins as Editorial Director for Children’s Fiction and I left because I couldn’t do the job with the twins, and I worked freelance for a long time, and then I started publishing books. I felt that I still had the job, but I’d lost my career, and I really did feel upset about that. Even though I loved my children, and I adored being a mum, and absolutely wouldn’t swap that time, I still missed my career.

There’s always a spiritual/mystical element in your books – could you talk about why that is?

I am really, really interested in spirituality and what people believe and why, and I think that’s why it comes into my books. It’s funny though, because my first four books written as Domenica de Rosa are mainly set in Italy and I said to myself right after that, “no more Italians and no more Catholics”, and I did stick to the “no more Italians” rule until Ruth book 10, which is The Dark Angel when they go to Italy. But the “no more Catholics” rule was broken the minute Nelson appeared, because I knew he would be a lapsed Catholic! And I just wanted to have all that, why people believe and how it affects their life. I’m not an atheist, I was brought up a Catholic. Now I would say I was a liberal Catholic, I guess, a freelance Catholic! I wanted to show that it’s with you all the time. I still get a great deal of comfort from prayer, meditation and those aspects. I have a friend who was brought up a Catholic like me and is now a Pagan, so I wanted to show her views respectfully through Cathbad and Nelson, who get on really well, they have a connection.

Something Nancy Mitford said always stuck with me. She said the people she really suspected were the people who talked about God as if his real name was Godfrey and God was just their nickname for him. I’m a little wary now, as I’ve got older, of certainty, where people think they know the answers, and I think initially Ruth’s parents, who were born again Christians, that’s their line, although book 14, called The Locked Room, the one that’s just about to come out, I think is nearing more understanding of her parents’ beliefs really, but yes, I’m very wary of that certainty.

I love all that doubt, and I love the fact that Nelson isn’t quite sure what he believes, but he’ll probably still say the Hail Mary if he has to. And Cathbad is a Druid but he’s also not above praying to his patron saints if he wants to. I suppose tolerance is what I’m aiming for in the books, that “many paths to God” line.

What made you choose crime fiction? Or did it just happen?

I think I was always interested in crime because I wrote my first book when I was 11, it was called The Hair of the Dog, which must have been something my parents talked about, but I didn’t know what it meant, but I did understand the revenge aspect of it – that the hair of the dog that killed you is the bit that makes you better.

And that was the plot, it was set in Rottingdean, which is right near where I still live. It was about a village where nothing much happens so they stage a fake murder there to try and get on the news, but of course the fake murder turns into a real murder. It wasn’t a bad plot, I don’t think. I was obviously already interested in crime, and there are two detectives, one is called Edgar Stephens, and of course I used the name later on for Edgar, and there’s a Max in it as well, so I even used that very name again in some of the books. So you know all the elements were there even when I was really young. I was a real fan of Enid Blyton and the Five Find Out-ers, and then I went through Agatha Christie and absolutely loved it. I’m a real fan as well of Nancy Spain, who wrote a book that’s been a big influence on me, called R in the Month. It’s set in a faded seaside town, and it’s about poisoned oysters. In the Brighton Mysteries I have tried to get that slightly dark, melancholic atmosphere that she gets in that book and she wrote some other really good ones, Cinderella Goes to the Morgue, Poison for Teacher, Death Goes on Skis. My mum had some of these books, I think she was very popular in the ’50s and my mum must have been a fan of hers, and she was an out gay woman at a time when that wasn’t very common, and she was often on talk shows and in the media. So I think I was influenced by her as well.

It was my husband Andy, who’s an archaeologist, who gave me the idea for The Crossing Places. It was a chance remark that he made when we were walking across Titchwell Marsh in North Norfolk, he said that prehistoric people thought that marshland was sacred because it’s neither land nor sea, but something in between, a liminal zone, a bridge to the afterlife, and that’s why you find bodies buried there, bog bodies. And almost immediately the plot for The Crossing Places, the first Ruth book, came into my head. Although I suppose at the time when I thought of Ruth as a character, I wasn’t even sure that it was crime. Ruth is asked by a police officer DCI Nelson to look at some bones he’s found, and those bones are 2000 years old, which is how she is drawn into the case. There’s the question “is it right to dig down into the past and disturb it?” That’s definitely a theme to the books.

When is your next Ruth book due to come out?

Early February. It’s called The Locked Room and it’s set during lockdown, which I thought would be interesting. I thought long and hard about whether to do lockdown in the books. But then, because I’ve written a book every year for the last 13 or 14 years it felt wrong to miss it out for a long term series. I think if I were writing a standalone I wouldn’t have set it in lockdown, but for a series I thought people might want to know what happened to those characters during that year.

Do you have to plot each book meticulously before you even start to write?

That’s changed a bit for me actually. So when I started The Crossing Places the plot did sort of come into my head as almost a complete book, but other than that I used to write a full chapter plan for my book, and set one line for each chapter. It was quite short. Some writers do immensely long plans, but I did one line for each chapter, but I would work to the end and I would know who did it. But the last four or five books, probably starting with The Stranger Diaries, my first standalone, I didn’t have a written plan and it was just in my head and when I wrote each chapter, I’d just write a little bit of the next chapter. I read a brilliant thing E.L. Doctorow said, that planning like that is like driving in the dark with your headlights on, you can only see a bit of the road, but you can make the whole journey like that.

Do you have a daily writing routine?

I’m quite disciplined. I don’t really like to write away from home, so I’m not one of those writers who takes their laptop to a cafe or on trains, but what I really like is to be in my little writing shed in the garden. I had only just finished it really before lockdown and it was an absolute godsend because it was somewhere else to go. I’ve got a cat called Gus, and at 8 o’clock every morning he goes and sits by the door of the writing shed and waits – he’s like my little furry conscience, so ideally I’ll go into the writing shed. I’ve got a coffee machine, I like coffee, I make myself a strong coffee and then I write. I try to write at least 1000 words a day. It’s not such a big target really, my books are between 80,000 and 90,000 words, so you’d think that in 80 days you’d have a book, but it doesn’t work like that. But I do try not to go back on it too much, I do try to do a different 1000 words each day until I have a manuscript and then I can go back and change it, so that’s how I work really. I try to do that in the morning, mornings are better for me and in the afternoon, do admin and all the other things that you have to do, but ideally 1000 words a day in my shed.

The Ruth books are written in the present tense, but the Brighton Mysteries are written in the past tense – how do you decide which tense to use?

It is really just what seems natural. We were talking earlier about different atmospheres, and I do wonder a bit if the different atmosphere of the Brighton Mysteries is because they’re in the past tense, with that slightly melancholic feeling. I didn’t really plan for Ruth to be in the present tense, but because I’d written those four books before under my real name, that sort of women’s fiction genre is often in the present tense, so I wrote The Crossing Places in the same way. Some people don’t like it at all, and I still get people saying they couldn’t read a book because it was in the present tense, some just don’t like it. It seems a bit of a shame not to read a book because of it, but there are people who don’t.

But the Ruth books have got real immediacy because of it, haven’t they?

Well, I think so. I think in some ways it seems to suit crime writing quite well because the reader is discovering everything at the same time as the writer. One thing that I love about crime as a genre is that you don’t read in a passive way, you read in a very active way because you’re trying to solve the crime, so I think it suits that very well.

The present tense can be quite hard to get right, the “she looks, she stops, she stares” etc because it’s like being repeatedly hit over the head with the action. So when you want to relax a bit or go into the past it can get a bit clunky and you can get a bit pluperfect – you know, “he had had had had had” something, so it can be a bit difficult! I think after the first book I did say to my editor that I might switch to the past and she said, “I think that would be fine too, to be honest I don’t think people would even notice, I think it would be OK” but then I thought maybe the present tense is the way I get Ruth – I do think that the fact that people have so connected with Ruth, which has been a wonderful thing, is partly to do with the present tense.

I think people like her because she’s not perfect and that was deliberate when I thought of her as a character, and what I liked was that she was going to be a woman who was very confident in her work as a forensic archaeologist but not so confident in other things. I feel she wouldn’t know how to drape a scarf! And hair is quite a thing – my daughter has lovely long hair and I always felt inadequate because I’m not very good at plaiting, whereas my German friend is amazing at plaiting and her daughter always had this wonderful plait that went round her head three times, and I would be in Assembly looking at the backs of their heads thinking Juliet’s plaits were a little bit, you know, uneven, thinking why can’t I be the sort of mother who plaits? Those moments are quite human I think, and people love that about Ruth, they can identify with her, because we all feel like that sometimes.

It’s been very touching to me to hear people saying that the books have helped them through lockdown. I decided to read the first Ruth book on my Facebook page at the beginning of lockdown, hoping that people might find it comforting and they did seem to really find it comforting, and there was that lovely exchange with readers saying “I look forward to 6 o’clock every night when I can listen to you reading” And it was really nice, I did feel a real connection to readers through that.

Misdirection is such an important theme in the Brighton Mysteries – are you playing with parallels between a magician misdirecting the audience, criminals misdirecting the police, and the crime writer misdirecting readers?

I think so, yes. When I teach plotting, that’s how I teach it. I start by showing the students a magic trick on YouTube (because I can’t do them myself!). I start by showing them a trick and I break it down and of course, that’s what you use in your writing, so you have the build up which should involve you getting an emotional attachment to the person, so it could be the magician doing their patter. Then you have jeopardy, when the magician shows you the sword and how sharp it is, and then you have misdirection, which sadly in the magician’s case often involves scantily clad women coming along! So you’d say, “Oh, look over there! There’s a woman over there. Look she’s not wearing any clothes!” while something else is happening, and as a writer, you’re doing things like, “Oh, here’s this new character. Maybe they’re a love interest for Ruth, but maybe they’re not.”

You can misdirect your reader in loads of ways, for example if you always call someone Grandad, the reader thinks “Here’s Grandad, oh that’s nice”, you forget his real name is James, and that he could also be the sinister Jim. So you have all those layers of misdirection, and then you get to raise the stakes, so that’s where after you’ve had one body, you maybe have another body and maybe have a third one, and then you get the reveal at the end when it’s all resolved. That’s all in the trick.

There’s a wonderful bit in a great book (and a great film) called The Prestige by Christopher Priest where he describes the trick in three parts: first of all, the magician shows you something, an ordinary thing, say it’s a pack of cards, and quite often he will get you to tap it. I mean, there’s nothing in that tap but you’re involved then, that’s why he makes you do it. Then he does something that makes it disappear. But that’s not the thing, the thing is when he brings it back, and that’s the third bit. It’s the involvement that makes the trick work, and in a similar way crime readers are actively involved in the trick, or mystery.

You have said that you think readers should be able to solve the mystery in the last few pages. Do you misdirect all the way through, but seed little clues that you hope some people will pick up?

I think even if readers don’t get it on the first reading it has to be retrospectively cursive, to use someone’s wonderful expression, so if you go back and re-read it, you should be able to see how everything was actually there for you to find. If you think of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, such a clever book still, when you go back and read it again you see that Agatha Christie has not cheated for one second.

There are lots of little tricks. One of them is to put the big clue in the prologue, because people always forget the prologue. There’s one book in which the author tells you the murderer’s name in the first line, he does tell you, but you forget. And you go back and you think “Wow, it was there!” And there are other ways that you can hide things. Lists are good, something in the middle of a list could be the big clue, but people don’t notice if it’s in the middle.

I think if somebody does guess you want them to guess at the right moment, just when there’s the reveal, you want them to think “oh yes!” but not before that, because that’s just annoying. And what annoys me a little bit in crime fiction (even the great Agatha does this a bit) is where their detective knows and says, “but I won’t tell you.” Why not?! Poirot keeps saying “Yes, I do know these things but I will not tell you” – and you think “If you know, say!” – they have to have the moment of revelation at the same time for the detective and the reader, so they shouldn’t keep it too secret.

In Northanger Abbey Jane Austen says something like the reader can tell by the “tell-tale compression of the pages before them, that we are all hastening together towards perfect felicity.” Isn’t that good? That reminds us of the joy of reading a real book – there’s a heightened excitement because you know you’re going to find out the solution soon. I think it’s a bit different on a Kindle (and I read a Kindle) where you know you’ve got 10% left, it’s not the same as seeing the physical pages diminish as you read.

Speaking of Jane Austen, Emma is a mystery in a way, isn’t it?

Yes, absolutely. And Miss Bates’s monologues have lots of clues in them. That’s another way of hiding clues, to have a so called boring, garrulous character like Miss Bates talking, talking, talking , talking – nobody takes any notice of what she’s saying, but her monologues are full of clues about Frank Churchill and Jane Fairfax all the time.

You’ve got police and amateur sleuths working side by side in the Brighton Mysteries and The Postscript Murders, and there’s a certain tension between them. Is that a useful plot device for you?

I think it is, and to be honest I don’t really know enough to write a straight police procedural in the way that Peter James does, where the investigators are just police, although actually I do have a police advisor who also advises Peter James, called Graham Bartlett, who was the Chief Superintendent for Brighton and Hove. He’s written brilliantly about policing Brighton and Hove, actually, and he does advise me on the police, but I didn’t meet Graham till about book three in the Ruth series. I think the first three have very little actual policing in them! I think I met him at a Peter James launch actually, and suddenly you get more policing in the books because I found out what they actually do! I did have a retired policeman help me with the first few books but because he had been retired a while, he might even be responsible for Nelson’s rather old-fashioned attitude, because I put that onto Nelson! But Graham obviously has retired young because he was a victim of police having to retire after so many years’ service, but actually he’s a young man and his son’s a police officer, so he knows what’s going on at the moment.

I quite like in The Postscript Murders, that you get the detective Harbinder’s irritation with the amateurs bumbling their way through. It is the fault of crime fiction to make us all think we know the answer. I know we’re both big fans of the 19th century – think of the Road Hill House case that Inspector Whicher solves, a hideous crime, with Brighton links as well – the amateurs were sure they could solve it. Wilkie Collins and Charles Dickens were guilty of this too, they were constantly writing to each other, trying to solve the case.

But you know, there is a snobbery about it, that intelligent, maybe middle class, people could solve it better than the working class officer. It is a class thing I think, it’s a kind of arrogance. And in the Golden Age as well you get bumbling police officers and then Lord Peter Wimsey comes in and solves it.

There’s an element of that in Sherlock Holmes too, isn’t there? Lestrade and the others at Scotland Yard are patronised, with Holmes as the great genius solving the case for them.

There is, and don’t forget that in Enid Blyton early on (and there’s no doubt that she is a crime writer), her police officer is a PC Goon, and there is a PC Plod. All right, these are Noddy books but even so, it does tell you something, the sense that working class people can never solve the crime, that you need a higher class, educated amateur to come in and solve it, there is a certain snobbishness about that.

I think I wanted to play with that a little bit in the The Postscript Murders where Harbinder, as a professional police officer, has this group of people who just because they’ve read a lot of crime or they’re literary, or they do the Times cryptic crossword and they’re good at anagrams, think they can solve the case. Obviously there is a bit where they do work together and they do reach an understanding, but even so.

I think with Ruth and Nelson it’s different because what Nelson really likes about Ruth is she’s on the same level, they’re both professionals, very good at what they do, and they respect each other. And although she does get involved in rather more murders than most archaeologists, she does try to confine herself to the archaeology and she’s actually not that interested in doing the police work.

Ruth respects what the police do, she doesn’t think she knows better, she’s just part of the team working on it.

Yes she does. I think one of the things that I’ve learned from Graham and from other experts, like Elizabeth Haynes who’s a really good crime writer and a civilian police expert, is that there’s a massive, massive team behind every crime investigation. They will talk to forensic soil experts and people like that.

Yes, I’ve learned a lot from reading Peter James, for example I never knew about forensic podiatry and gait analysis before reading his Grace books.

Exactly! I’ve met his forensic podiatrist, Dr Haydn Kelly, and what a fascinating guy he is – he told me how you can tell if someone was carrying a body upstairs! I love those little details. A forensic archaeologist told me quite early on, and I’ve used it in a few books, that nettles are often a sign that there’s a body there, because you can’t get nettles without some sort of human interaction, so it could just be someone weed there, but it could be something buried there. I did an event with a terrific Scottish writer called Lin Anderson, who writes about a forensic scientist, and she said that on the Jacobite graves in Scotland, on the hills, no heather grows on those graves, it’s just grass. And sometimes there’s a dip where there’s a grave, because imagine there’s a body, when its rib cage goes, then there’s a dip in the earth. So it’s fascinating reading the landscape. I like that behind every crime there’s a whole team of different experts, all working together to solve the crime, that’s something I have learned from talking to police officers.

Are the police helpful when you’re researching for a book?

I’m always amazed at how nice people are about it, you know. Graham is, particularly. I’ll send him something and I’ll say, “could this happen?” Clearly he wants to say “no, not in a million years” but he’ll say, “well, that’s a bit unusual, but I can see how that might happen this way.” For example, there’s an armed siege in The Night Hawks and I said to him, “I want to have an armed siege in it, can I send you the chapter?” And I did, and he’s always really nice, but he said “actually, that’s not how that would happen. How it would happen is Nelson would have a firearms commander who would be taking their advice from somebody else.” And he said, “actually, I can see how well that would work in the book, because Nelson would be really frustrated by that” and he made that chapter so much better because you have Nelson being frustrated because he’s not in charge, and all the decisions are being taken by someone not at the scene so they can be totally dispassionate, and that actually does make it a more dramatic scene, and he understood that totally, but he’s a writer himself, so he understood about the fictional tensions.

But police officers are really generous, and archaeologists have been super generous. In one of my books I had to find a plant that only grew in a certain place. Of course I could have made it up but it’s nicer not doing that, and a Brighton archaeologist friend of mine, Matt Pope, put me in touch with a forensic botanist who found this fern that only grew in a certain place. And in the book there were these spores on the body that could only have come from this place.

For The Woman in Blue, which is set in Walsingham, I actually went on a pilgrimage to research it and I was very honest with the priest who was leading it, and I said I’m obviously going to be very respectful and I understand the prayer experience, I’m going to enter into that, but I’m also researching a book, and he was so keen, in fact he was almost too keen! We’d be in a chapel and everyone would be lighting candles and we were all very silent and Father Kevin would be shouting at me “Dom, do you think you could kill someone with a thurible?” And everywhere we went he was saying, “oh, I can see this would be a good murder!” Father Kevin does get a mention in that book because he was really helpful. I think there’s something about a crime novel that does get people really interested, despite themselves.

It’s in our head, isn’t it, as we’re hastening together towards perfect felicity in the books? We’re trying to solve it and we want to work it out. I think some Golden Age mysteries are just a puzzle without having much else, a poisoned chocolates case, you know, whereas probably what modern crime fiction does quite well is it’s also really involved in the characters. I do think they have more depth. I think it’s great to have the puzzle which everyone loves, but also the human element and the development of relationships in a series.

That’s the way of keeping a series fresh, isn’t it? You’ve got a new crime plot each time, but you need to continue the personal lives of the recurring characters, and that keeps people coming back for more.

I do think that’s true, and I do think that is why people like series, the development of the characters. Miss Marple, bless her, doesn’t change at all, I don’t think, during the course of the books. I’m one of the twelve writers being asked to write a new Miss Marple story for her centenary next year, which is such an honour. One of the better things about it, what it makes it possible, is she’s not always centre stage in all the books she’s in, sometimes they’re first person by someone else and she is there in the background, so that makes it a little bit easier, but I think generally speaking, nowadays we do go to series because of the characters, they keep us coming back. And they say there are only so many plots, don’t they? And I don’t think a writer can think of a massive killer twist every time, but what makes each book different is the characters and how they interact and how they’re growing. Ruth has a child, and that’s quite a nice way of being able to see time passing. When I started the last book I thought “Kate’s nearly 11, she’s going to be going to secondary school soon” – that’s the same shock you have with your own children, that sense of time passing and characters ageing.

Nelson’s mother Maureen is one of my favourite characters, but we haven’t actually seen her in person since Dying Fall, and I’ve been waiting to bring her back in, and also there was a slight theme in that book about parents being actual people as well, because Ruth is having discussions with her bereaved father, where he’s moving forward with his life, and so I wanted that to be part of that book. So it was quite nice to bring her back in, and Ruth’s brother, as well, reappears in that book. We haven’t seen him since The Outcast Dead and we’ve never met Judy’s parents, I think we might have to meet them. It’s nice when people come in and out.

With writing a series you live with characters over many years – what does that feel like, do you feel that they’re almost real people?

Yes you do, in a way, although you try and remember they’re still words on a page, really. But definitely, and I’m certainly attached to Ruth and Nelson in a way that means I can’t ever really just treat them as words on a page.

One of my favourites to write is Justice, the heroine of my children’s books, and that’s because she’s very much based on my mum and on the stories she used to tell about being at boarding school (she’d write stories as well.) Justice has many of the elements that my mum had as a character, resilience and bravery, she’s actually a great person to be with and she cheers me up a lot, so I write a Justice chapter every Friday to cheer myself up. So in some way she’s my favourite character to write, whereas Cathbad I do like as a character but I find it hard to write from his point of view, and I’ve done that very rarely in the books. There’s a little bit in the new book, and there’s a bit in Dying Fall from his point of view, and I wonder if that’s because, although I respect his world view I don’t totally share it, so it’s quite hard to write without looking at it from the outside, you wonder how much he really does believe, and if you’re being him, you have to know.

Also with Ruth’s boss Phil, who is quite an unappealing character really in the books, suddenly in The Lantern Men I had not even a chapter, just a brief bit, from his point of view, the first time I’ve ever been his point of view, and it totally changed my feelings towards him. I’d always been outside sneering at him when he grows a beard, and because he loves being on TV, but when you’re him you can’t take that slightly sneery outside tone. He’s cycling home and they’re having a dinner party and he stops to buy something for the dinner party and he thinks “I’ll get some After Eights ’cause my mum used to buy those for dinner parties” and suddenly I think “Oh Phil!” and feel more sympathetic towards him. It took me twelve books to understand that!

With the Ruth series do you ever wonder how you’re going to end it? Do you intend to end it?

It will come to an end, or at least there will be a pause. I couldn’t see that pause, but funnily enough, writing book 14, The Locked Room, set during lockdown, did change something in me and I could certainly see how it was going to end, so now I can. And it won’t be that far off. But it might not be an end forever.

Does it feel difficult to contemplate letting go of a series?

It seems quite scary, but I have so many other ideas for books, different projects, different series, different characters.

You are very prolific, and quite unusual in having several distinct detective series.

That is partly because I do have lots of different ideas and I’ve just been so lucky that my publishers have more or less gone with my ideas. At the moment I’m starting a new standalone, with Harbinder in it, so she sort of is a series, I didn’t mean her to be, but she’s turning into a series.

When I had the idea for the Brighton Mysteries, which are partly based on my Grandad, who was a musical entertainer, I did hope my publishers would say “Oh, that’s great, so you can write a Ruth book one year and then a Max book the next year” but actually they said “Oh that’s great, you can do two a year”! So that’s how I got into the two books a year, and I don’t want to keep on doing that forever, but I do have lots of different ideas, and lots of different characters wanting to come out. So maybe there will be a break from Ruth, but maybe there’ll be another character people like as much as Ruth, you never know.

Do you avoid reading people who write about Brighton or Norfolk?

Not really. When I’m in the middle of writing about the ’50s, I do read people like Monica Dickens, who get into that ’50s tone a little bit. I suppose I might not read books that have archaeologists in them, there seem to be a few around now, so maybe I’d steer slightly clear of those, especially when I’m in the middle of a book. I just read everything really, and I quite often have an upstairs book and a downstairs book, so it depends where I am when I’m reading! I love biographies, I like history, I love C.J. Sansom, another Brighton writer, who writes those amazing Tudor mysteries.

Did you have Graham Greene in the back of your mind when you wrote the Brighton Mysteries?

Yes, a bit. I love Graham Greene, Brighton Rock is amazing, but my favourite book of his is The End of the Affair because it’s about belief. And The Power and the Glory, that sense that somebody can be an unworthy vessel but still be a really good priest. Also Evelyn Waugh, Brideshead Revisited, that moment at the end when Lord Marchmain makes the sign of the Cross, and Sebastian, who’s holy in a way that really pious characters like Lady Marchmain can never be. I was very struck by A Married Man by Paul Piers Read and the idea of redemption in that book. I like redemption in a story, particularly when it’s unusual, like the moment at the end of Brideshead when Charles Ryder kneels down to pray – everything isn’t better from that moment, but actually there is a moment of redemption, isn’t there?

What do you read for pleasure?

I do read a lot even though I think I’m a slower reader than I used to be. Now I read before bed and I always have to have a book with me. I read a lot of crime fiction, partly because a lot of it’s now sent to me to read, but a lot of it I would read anyhow. I’m a big fan of Lesley Thomson, who’s a crime writer, and a good friend of mine as well, she wrote the Detective’s Daughter series. William Shaw I really like as well, Sarah Hilary, Jane Casey’s Maeve Kerrigan series, she’s a great character, Maeve. I’m a big fan of Liane Moriarty, and American writers like Alison Lurie and Anne Tyler. I think David Lodge is one of my favourite writers, Nice Work is one of my favourite books. I’ve just read Elizabeth Day’s Magpie, which I thought was really, really good, so I’m trying to keep up with stuff. I re-read Georgette Heyer, whenever I go on a ‘plane I take a Georgette Heyer book just in case.

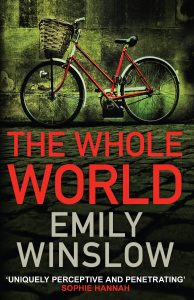

Elly Griffiths wrote four novels under her own name (Domenica de Rosa) before turning to crime with The Crossing Places, the first novel featuring forensic archaeologist Dr Ruth Galloway. The Crossing Places won the Mary Higgins Clark award and three novels in the series have been shortlisted for the Theakstons Crime Novel of the Year. The Night Hawks (Ruth #13, published in February 2021) was number two in the Sunday Times Top Ten Bestsellers list. Elly also writes the Brighton Mysteries, set in the theatrical world of the 1950s. In 2016 Elly was awarded the CWA Dagger in the Library for her body of work. Her first standalone mystery, The Stranger Diaries, won the 2020 Edgar award for Best Crime Novel. The second, The Postscript Murders, has recently been shortlisted for the CWA Gold Dagger. Elly also writes A Girl Called Justice, a mystery series for children.

A couple of months ago I read the interview with Elly Griffiths on this blog and was inspired to buy one of her books. I thought I would start with the Brighton series and intended to buy the first book but (owing to not paying attention or being an idiot) I bought the most recent by mistake – Now You See Them. I read it at once and spent quite a long time thinking “there’s a surprising amount of backstory here for the first book in a series” before I twigged! At least I proved that there’s no actual need to read Elly Griffiths in the right order as the book was extremely enjoyable as a stand alone although I’m now going back to start at the beginning properly. I liked the Brighton setting and particularly the sense of time with the Mods and Rockers battling on the sea front. The pervasive presence of stage magic was also rather nostalgic for me – I’m of the generation that grew up with the Paul Daniels magic show being ubiquitous on TV and I imagined the character Ruby’s hit programme as being along those lines.

A couple of months ago I read the interview with Elly Griffiths on this blog and was inspired to buy one of her books. I thought I would start with the Brighton series and intended to buy the first book but (owing to not paying attention or being an idiot) I bought the most recent by mistake – Now You See Them. I read it at once and spent quite a long time thinking “there’s a surprising amount of backstory here for the first book in a series” before I twigged! At least I proved that there’s no actual need to read Elly Griffiths in the right order as the book was extremely enjoyable as a stand alone although I’m now going back to start at the beginning properly. I liked the Brighton setting and particularly the sense of time with the Mods and Rockers battling on the sea front. The pervasive presence of stage magic was also rather nostalgic for me – I’m of the generation that grew up with the Paul Daniels magic show being ubiquitous on TV and I imagined the character Ruby’s hit programme as being along those lines.