Contributor: Rosalind Esche

One of the most popular traditional stories reproduced in children’s books during the 19th century was The Children in the Wood, also known as The Babes in the Wood, first published in Norwich as a broadside ballad by Thomas Millington in 1595 with the title The Norfolk gent his will and Testament and howe he Commytted the keepinge of his Children to his own brother whoe delte most wickedly with them and howe God plagued him for it.

What a sorry little tale this is. For those of you mercifully unfamiliar with it, it relies on that stock villain, the wicked uncle. The parents of two small children both die at the same time (somewhat irresponsibly, in my view) and on their joint deathbed consign their hapless offspring to the clutches of their uncle. To be fair on the chap, he looks after them for a while until he reads the terms of the parents’ will and discovers that he would benefit to the tune of several hundred pounds on the occasion of the children’s untimely deaths prior to attaining their legal majority.

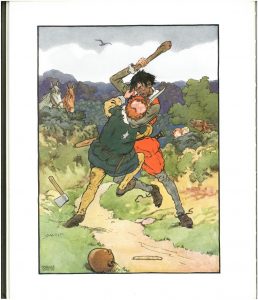

This is when things really start to go downhill for the eponymous babes. The uncle hires two “sturdy ruffians” to take them into the woods and kill them. One of the villains relents on hearing the innocent, lisping prattle of the two babes, and refuses to carry out the murder; a quarrel ensues and the “milder” cut-throat kills the other, in front of the (presumably traumatised) babes.

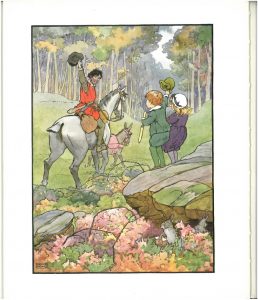

He tells the children that he will bring them some food, and, convincing himself that a passing traveller will discover them, leaves them alone in the woods, never to return.

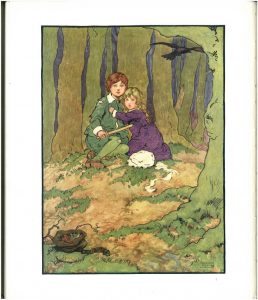

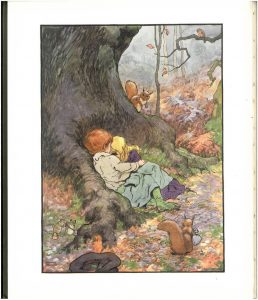

The children wander through the woods, and eventually, weary and forlorn, they sit down beneath a big oak tree to rest.

As dusk falls they settle to sleep. Relief in the form of a passing traveller never arrives.The children starve to death. It’s as stark as that. You will be glad to hear that all kinds of disasters befall the wicked uncle and he dies in prison.

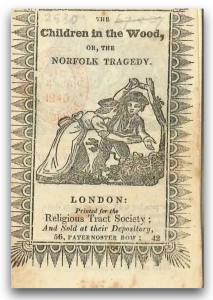

However, perhaps I do the purveyors of this sensationalist literature a disservice. I was interested to see that one of the many 19th century copies of this grim children’s tale is entitled The Children in the Wood, or, The Norfolk Tragedy.

Local folklore has it that the events told in the many versions of The Babes in the Wood originally happened in Wayland Wood, reputedly the third oldest wood in England, dating back to the Domesday Book, in which the Wayland Hundred is referred to as Wane-lond. Various theories have been advanced as to how the legend of the babes came to be associated with Wayland Wood, one being that there used to be a carved wooden overmantel in the nearby Elizabethan manor house Griston Hall, where the uncle is said to have lived, which depicted the story of the babes.

Apparently the tale of the babes in the wood has never been associated with any place other than Norfolk during its long folkloric career, so perhaps we have a real Elizabethan crime which morphed into legend. Inevitably local tradition has it that the ghosts of the murdered children haunt Wayland Wood, hence its popular name “Wailing Wood.” The village signs at both Griston and nearby Watton depict the story. When in 1879, the tree under which the babes had reputedly been abandoned was struck by lightning and destroyed, the popularity of the legend had grown to such an extent that people visited the site, hoping for souvenirs.

If it seems to stretch our credulity that two small children should be lost in a wood for so long that they starved, this arresting account by a local may bring home to us the desperate plight of the children:

Having known this wood all my life I can remember my father taking me to the keeper’s cottage when I was about seven and asking the keeper if he would show us the tree under which the babes were reputed to have been found, buried by a robin covering them with leaves. He escorted us far into the wood and stopping by the stump of a large tree, informed us that this was where they died, the tree having been destroyed by lightning in August 1879. As we made our way back to the road I realised how difficult this would have been without our guide, with so many overgrown paths criss crossing each other in all directions. At this time it was not unknown on shooting days for one of the beaters to get lost in the wood during the last “drive” of the day, with darkness falling fast. Occasionally it meant he had to wait until morning light to find his way out. This would not happen today, as one can hear the continuous roar of traffic passing along the road and head towards it. None the less 30 years ago, when “birding” in the wood with a naturalist friend, we came upon an elderly man whom I knew very well, but owing to his dishevelled appearance did not recognise at once. He had grown a beard, was painfully thin and obviously so weak he could hardly stand. Although he managed a slight movement of his lips, no sound was forthcoming and we realised he was in a very serious condition. Informing the police, we were surprised to learn that he had been missing for three weeks and that they had spent many hours searching for him. As he lived alone, arrangements were made for him to be cared for in a Thetford home and when I saw him a month later he thanked me for saving his life. It appeared that he had strolled far into the wood one afternoon and was unable to find his way out again, but it was not certain if he had been there all the time.(http://www.historyofwatton.org.uk/wattonttages/053.htm)

So perhaps this unpleasant little tale has its origins in history rather than in some warped imagination. Nevertheless, the fact is that Victorians loved this kind of sensational, sentimental storytelling. The prevalence of this dismal tale as a staple of children’s picture books testifies to its assimilation into the popular imagination. Indeed, the expression “babes in the wood” survives to this day as shorthand for inexperienced innocents making their way (or not) in a wicked world.

It’s interesting to speculate on this “evil uncle hires two murderers to despatch troublesome children” story – how far back in the mists of time does its folk tale origin reach? It almost certainly pre-dates the Norfolk version, having its roots in inheritance struggles for money and power. Did the stock character of the wicked uncle just happen to be reinforced by a real crime in Norfolk some time in the 16th century? And for those of us troubled by a nagging sense of familiarity, could the existence of such an archetype lend credence to those Richard III advocates out there who claim him as a victim of Tudor propagandists? Could those canny Tudors have been tapping into folk imagination to besmirch the Plantagenet’s name? Just how far back do wicked uncles trace their heritage? But I digress …

Still, it’s not all bad news. Imagine my delight when I came across the following antidote to all this misery, with the stirring title:

Perfidy detected! or, The children in the wood restored, by Honestas, the hermit of the forest

with the following explanatory subtitle further down the title page:

who were supposed to have been either murdered or starved to death, by order of their inhuman uncle ; being the continuation of The history of the children in the wood.

The logistics of this reworking are a bit hazy; not only do the babes survive, but even the dead parents aren’t dead after all. No matter, someone else had obviously had enough of this wretched story and decided to set everything to rights again, even if it meant glossing over minor technicalities of logic and plot integrity.

Postscript

I had one of those satisfying connection moments, when I read that it was a robin who covered the children’s bodies with leaves – could it have been Cock Robin himself? Before he was brutally murdered, obviously, in that other cheery children’s tale so beloved of the Victorians.

Illustrations are from the following books held in Cambridge University Library, which may be requested to be consulted in the building.

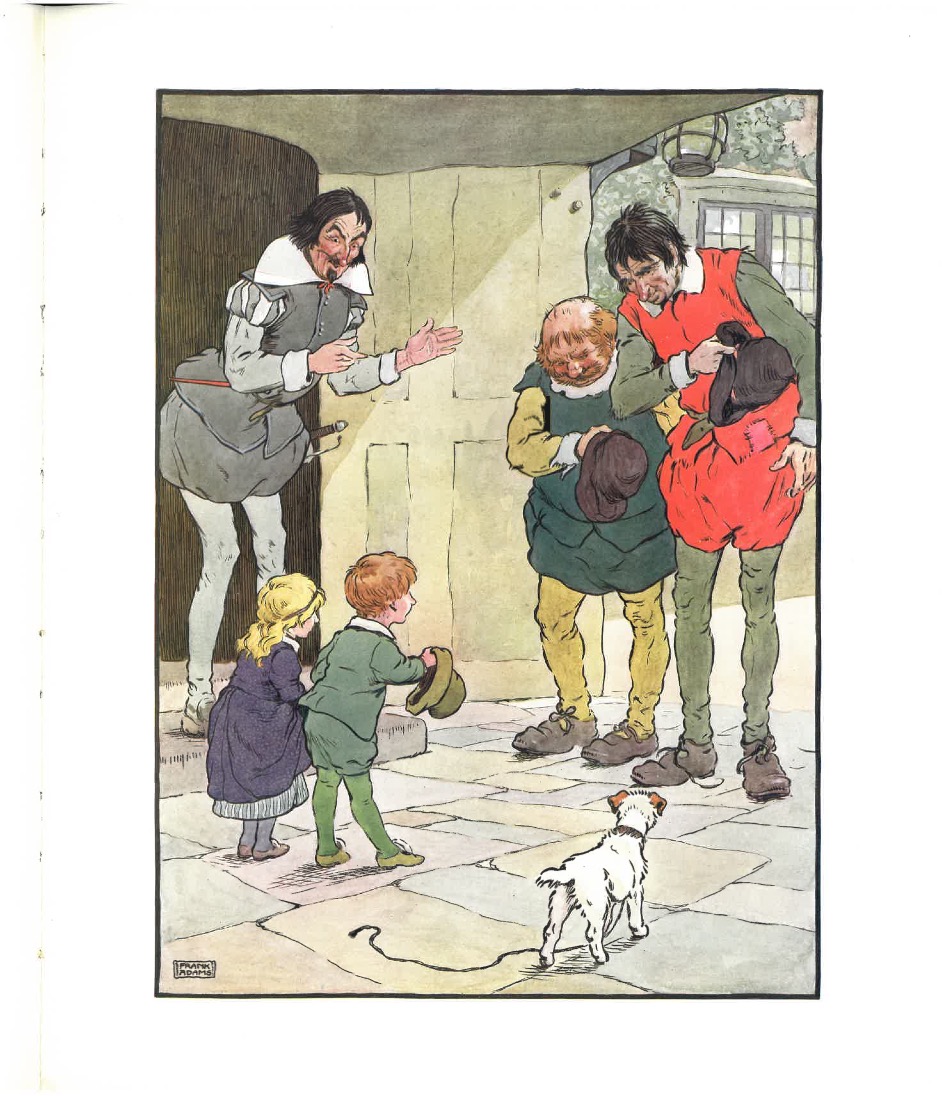

The Story of the Babes in the Wood, illustrated by Frank Adams. Published London ; Glasgow ; Bombay : Blackie & Son Ltd., [1904?] – University Library classmark 1904.11.86

The Children in the Wood, or, The Norfolk Tragedy. Published London : Printed for the Religious Tract Society, and sold at their Depository, [18–] – University Library classmark CCE.7.67.27

Thank you for another fascinating treasure from the tower. What a frightful tale with all manner of psychological and folkloric underpinnings. I particularly enjoyed author Rosalind Esche’s musings on how the Tudors might have used the popular but awful tale of the babes in the wood to calumniate Richard III.

The illustrations are a wonder to behold, notably the image of the “good” cut-throat gaily doffing his cap to the babes (the boy reciprocating) as he rides away, having convinced them, and himself, albeit briefly, that he’ll soon return with food.

We’ve all, I imagine, felt lost emotionally, psychologically, at times. And who hasn’t on occasion been lost in a maze of streets or on unfamiliar terrain or, why not, in a wood? As we walk in today’s world of GPS, facial recognition systems, surveillance, and location-sharing apps, heads bowed, eyes riveted to Google Maps, are we not in danger of missing unexpected delights, and of walking unheedingly past the babes in the wood?

How could they ?! Such a dreadful story paired with the sweetest sentimental illustrations – who ever thought that was suitable for young children? Surely Victorians had more appreciation of what starving to death might actually mean than we do. Well, there may be a lot of tat on CBeebies, but I’m voting for Tracy Beaker any day, even the Clangers, rather than murder, and that goes for the Brothers Grimm too.

What a wretched tale indeed! Having never read the story, I found myself totally appalled and haunted by the fate of these darling little children and the illustrations by Frank Adams. The sight of them waving off their protector, somewhat cheerily given what they had just witnessed, followed by the little boy, with his ripped shirt and broken wooden sword, his arm around his sister. Lost and left to to starve!!! What was wrong with Victorian minds?! I certainly hope there is not an ounce of truth to the story. However, I think I will steer well clear of the ‘Wailing Woods’, should I ever find myself close enough for a stroll.

Despite the shock, this was certainly an interesting read. Good to know the history behind the expression ‘babes in the wood’ as well.