Contributor: Rosalind Esche

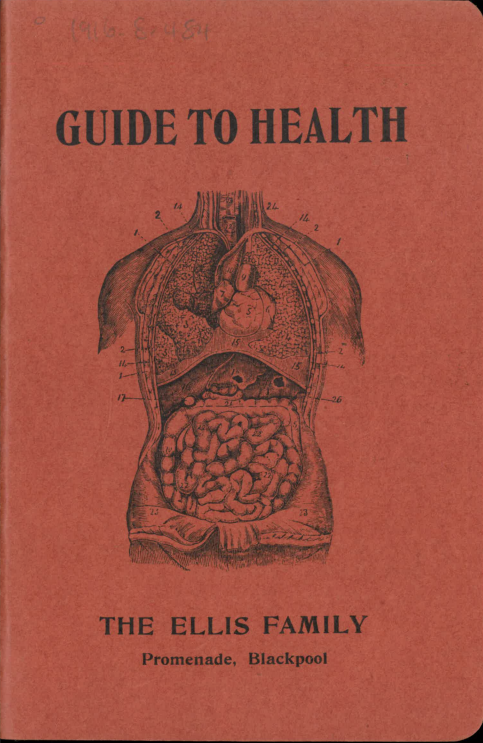

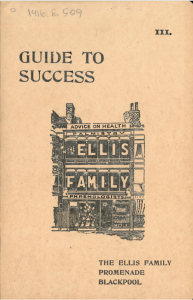

When we think of seaside promenade attractions, such as fortune-telling, palm-reading and so forth, we tend to imagine stripey booths and bead curtains. When I worked on the Tower Project at Cambridge University Library I catalogued a series of pamphlets written and published by the Ellis family, who advertised themselves as phrenologists and publishers (but who dabbled in a great deal more than that), and had impressive premises on the promenade in Blackpool.

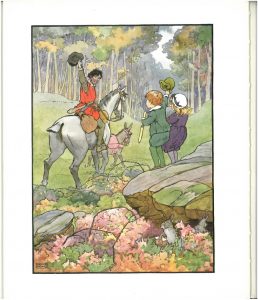

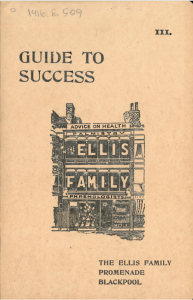

The Ellis family establishment

Note the heads either side of the word “Phrenologists” above the door, and the slogan “Advice On Health” on the roof, between two particularly striking hands, palms facing outwards, in front of the chimneypots. Clearly the Ellis family, Ida, Albert and Frank, were successful enough to operate from a solid building rather than a beach hut. The 1911 census records that Albert and Ida Ellis (husband and wife), Frank Ellis (brother) and Annie Edwards (domestic servant) occupied a house with 11 rooms, not counting, as instructed on the census form, “scullery, landing, lobby, closet, bathroom, nor warehouse, office, shop.” Looking at the illustration of their promenade premises (81/82 Central Beach, Blackpool) it is likely that the consulting rooms were on the ground floor and they lived in 11 rooms above on two further floors – quite an establishment. Albert originated from Canterbury, and Ida from Suffolk, but when they first arrived in Blackpool I could not discover. Blackpool, as a popular seaside resort, offered excellent opportunities for a business such as theirs. Albert and Ida were 42 and 43 respectively at the time of this census, and had been married for 21 years. All three Ellises give their occupation as Palmist/Phrenologist and record that they work “at home.”

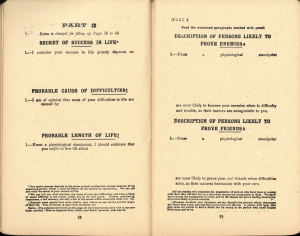

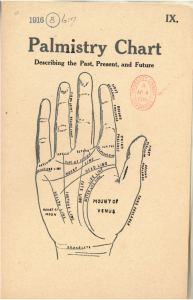

Each family member specialised in their own particular skill: Frank in physiognomy, Albert in graphology and phrenology, Ida in palmistry, crystal gazing, automatic writing and psychometry. When customers consulted the Ellis family they would receive a booklet described as a “chart,” published by the Ellises themselves, packed full of information, with blank spaces in which a personal reading would be inscribed, with appropriate advice.

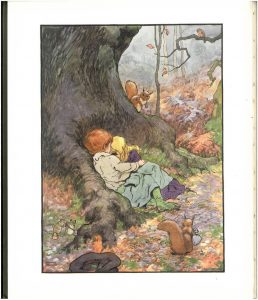

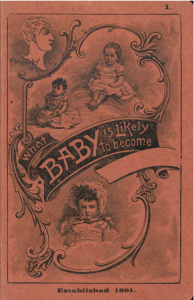

Even babies could be taken to a consultation and have their own chart filled in with their potential characteristics, personality, skills and so forth.

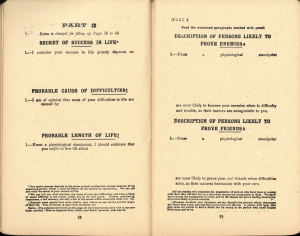

Each chart has an index to character, so that after the initial phrenological consultation, the relevant Ellis, presumably Albert in this case, would mark in pencil numbers listed in a sort of tabular key at the front of the booklet, which the customer then relates to the characteristics correspondingly numbered in the following pages. After that there are pages with blank spaces in which the Ellises would write customised advice (for an extra fee) on your health, occupation, relationships and so forth, even describing “persons likely to prove enemies.” On a page headed “Summary of mental powers” the seven options provided include “You have inherited a very inferior nature, and will not think for yourself. You are low and vulgar in your habits.”

I can’t help thinking that anyone diagnosed in this category would feel pretty hard done by, parting with ready cash only to be told they were vulgar and inferior. The Ellis family obviously didn’t pull their punches; perhaps such brutal truths bestowed an air of authenticity on their readings.

The Ellises knew that they had to keep clients coming back for more. In their “Advice worth following” on p. 23 of “Stepping stones to success” they explain:

“We would like you to consult us every year, because science is advancing so quickly that we are continually adding new features to our book. This enables our clients to obtain the latest information about themselves we can give, and also an opportunity to compare one chart with another, and thereby see what improvement has been made.”

Good idea to let your clients know that you keep up with the latest research in your field, there’s nothing so reassuring as a commitment to professional development in health practitioners.

In the lists of their books for sale at the end of their pamphlets, I noticed that the Ellises had initials (F.B.I.M.S.) after their names, which my research tells me stood for Fellow of the British Institute of Mental Science. Apparently the British Institute of Mental Science was founded by Albert Ellis in 1891, initially to offer postal tuition, later issuing diplomas and certificates.*

Thanks to information provided by Mark Ellis, a descendant of the Ellis family, we know that Ida ran the consulting rooms at these premises while Frank was busy running the promenade business.

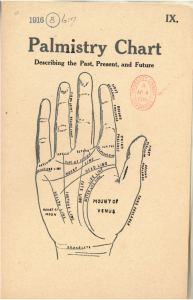

The Ellises are careful to qualify their claims to scientific authenticity in “Notice to clients” at the beginning of “Palmistry chart” with an ingenious explanation of why a client’s life may not unfold as read in their palm:

“It must be thoroughly understood that palmistry does not teach that things must absolutely occur, but that they possibly may unless steps are taken to hinder their occurrence. Thus it will be seen that if a voyage is marked on the hands, and efforts are made to hinder such an event, the mind will gradually register on the hands that the voyage was hindered, or the sign may fade away; whereas if events had taken their ordinary course the voyage would have been undertaken.”

In other words, anything could happen.

The allusion to science is a canny ploy by the Ellis family – phrenology occupied a curious position in the public imagination during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, peddled on the one hand by fairground quacks, while being the subject of genuine academic research by respected thinkers on the other. Significant British phrenologists included the Scottish brothers George and Andrew Combe, who established the Phrenological Society of Edinburgh in 1820. This group included such well-respected luminaries as the publisher/author Robert Chambers, the astronomer John Pringle Nichol, the botanist Hewett Cottrell Watson and psychiatrist and asylum reformer William A.F. Browne (who took part in debates at the Plinian Society, of which Charles Darwin was a member). However, phrenology enjoyed a chequered career as a serious academic discipline, was rejected by the British Association for the Advancement of Science, and was eventually designated a pseudoscience.

We may scoff at the Ellis family’s methods, but aren’t they just cashing in on that enduring human need – to be listened to? Clients could enjoy the time and undivided attention of Albert, Ida or Frank at a consultation. What, after all, are psychiatrists and counsellors, if not people who will listen and dispense advice, for a price? And a much higher price than the Ellis family’s fees. Perhaps we should see the Ellis family as the poor man’s psychoanalysts, the working class alternative to the psychiatrist’s couch? People then, as now, were hungry for the promise of self-improvement, success, personal happiness and fulfilment.

As for Albert, Ida and Frank, the bumps on their heads would surely have denoted sharp business brains. It feels a bit like booking with a certain budget airline, reading Ellis family booklets – you’re forever coming across extra charges.

“If at any time you require a more complete guide to success, you should send this book by post to the address on the cover, and enclose ten shillings.”

“We shall be pleased to fill up any portions of this book at any time from your photo or handwriting or impressions of hands. Our fee for doing so through the post is one shilling for each part.”

“Palmistry by post or by personal interview. If by post it is necessary for the client first to send 6d. for a bottle of Transferine, a liquid composition for the purpose of making impressions of hands. Fees according to length and detail of description.”

I can’t help wondering what the ingredients of Transferine were – Mark Ellis told us that it was invented by Frank as a removable (washable) type of ink for sending hand prints by post.

The Ellises were careful to preserve their intellectual property, too. On the first page of all their publications is the following warning:

“This chart is copyright, and legal proceedings will be taken against any person or persons who publish any portion of it without the written consent of the publishers, who have obtained an injunction and costs against a character reader who infringed the copyright of one of their charts.”

In other words, look out, any other “mental scientists” out there, and make sure you don’t impinge on the Ellis family turf.

*Witchcraft, magic and culture 1736-1951 by Owen Davies (published Manchester UP, 1999) – this book is held by Cambridge University Library at this shelfmark: 198.c.99.179

These pamphlets are housed in the tower of Cambridge University Library at the following shelfmarks and may be requested for consultation in the Library building:

- Aids to self improvement. Classmark 1916.8.483

- Guide to fame and fortune. Classmark 1916.8.572

- Guide to health. Classmark 1916.8.484

- Guide to success. Classmark 1916.8.509

- Palmistry chart. Classmark 1916.8.617

- Stepping stones to success. Classmark 1916.8.508

- What baby is likely to become. Classmark 1916.8.621