Emily Winslow talks about writing crime fiction

Image courtesy of Jonathan Player

Do you think of yourself as a crime writer or as a novelist who happens to write about crime?

I think of myself as a crime writer, but with the very broadest definition of crime. So I’m happy to have my books always be about figuring something out. I’m happy for them to always involve extreme situations, like dealing with a murder. In that sense they’re crime, but they won’t necessarily always follow a certain format.

Some might think that writing, and indeed reading, crime fiction indicates an unhealthy attraction to the dark side of the human psyche. But is it actually a healthy way of exploring fears and dangers in a safe place?

Oh 100%. I struggled with this myself when I was younger and I used to spend a lot of time in the true crime section of the library. I thought, what am I doing? What does this say about me that this is my entertainment? Am I a sadist or something, what’s going on here? I’ve thought about it and I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s perfectly fine, and that when I spend time reading about it or writing about it, the focus isn’t on the crimes, the focus is on coping with the crimes, responding to the crimes, regrouping and rebuilding after something immense and world-changing has happened. If you look at most crime novels, they don’t lovingly detail the violence chapter after chapter. Something horrible has happened and then you see people trying to cope and recover afterward, and try to make something out of it and try to do the best they can to fix what’s fixable. I think it’s extremely healthy.

Would it be fair to say that you are interested in the puzzle and the crime, but you’re even more interested in how people cope with it, and the psychological ramifications of what happened?

Yes, and the psychology of what causes crime too. I know that a lot of times murder mysteries set up at the beginning a lot of different character motives. That’s one standard way to organise a crime novel and very entertaining; you realise this person would get money, this person would get freedom… But for me a motive is not enough, because to kill somebody is such a psychologically horrifying thing to do. For me, it’s not enough to say this person would benefit from the victim’s death, it’s who would benefit from their death and could actually bring themselves to do it. Also, how does it change them afterward now that they’ve done it? All of that psychology is really important to me. Motive is only step one.

You said in an article for CrimeReads in 2018 that to read or write crime fiction is to practise hopefulness. Could you elaborate on that?

Well, it’s about coping and recovering, and about building something new, when the thing you thought was going to be your future has been destroyed and taken away. For me personally, the fact that I spend so much of my life, so much of my reading and my writing, rehearsing that pattern—something terrible happens, and then you deal with it and you make something new—just living that over and over again in my mind has been helpful to me. When I experience struggle in my own life I realise okay, this is the struggle, this is chapters one, two and three, and then we’re going to start coping, and then there will be something new that’s going to come out of this. I think that reading and writing this stuff is good practice for healthy psychology in life.

And is it a safe place to rehearse things that might never happen to you, but you’re afraid of them, and it helps you cope?

Yes, absolutely. So many of our fears will absolutely never come to pass, but it’s really interesting to think about what if they did. What could be done in the wake of that? And it’s just reassuring to know there are things that I can do, things that will happen after.

You use multiple narrators in your books with differing points of view – are you particularly interested in narrative unreliability?

I’m interested in narrative unreliability in books because it represents normal human narrative unreliability. All my books have multiple first person narrators; we have the detective point of view and sometimes victim points of view, and sometimes murderer points of view or witnesses and bystanders. It’s interesting that it takes all of them to tell the story. That’s where the title of my first book comes from, The Whole World. No one character has the whole story. You need all of them to understand the whole thing.

None of us have the whole story about anything; we’re each just one voice adding to the whole. So for me, it’s not just something that I like in book characters; it’s a personal philosophy that’s deeply important to me. My books are sometimes criticised for it being difficult to tell who the main character is. And I understand that that can be a flaw from a literary perspective, but for me it’s completely deliberate, because my whole point is that there is no main character. We’re all just coming in and out of the story, which is central, but nobody gets to be the one star.

And using multiple narrators enables you to demonstrate how memory works?

Memory is one of my favourite themes in all the world, and how memory changes over time. Different memories belong to different people, and yet they’re all looking at the same thing. Memory is, I think, one of the most fascinating human things to think about.

You worked for Games magazine as a creator of complex logical puzzles – is that skill useful for creating the puzzle element of your crime stories?

Puzzles are deeply profound to me in a lot of ways. First of all, my dad was a lawyer and then when I was around seven years old he quit being a lawyer to invent board games and puzzles in the basement. It was amazing; my friends and I, we grew up hanging out in my dad’s workshop and using all his tools and things like that. We were his game testers. That was a very important part of my growing up. So puzzles came very naturally to me.

Philosophically, what I love about puzzles is you start out with something that superficially seems impossible. Even a crossword puzzle looks to me that way; I look at it and say “there is no word that can fit here”. Do you know what I mean? It says there’s a ten-letter word, I know Q is the ninth letter, and I’m just looking at it thinking there is no possible word. Eventually when I figure it out, I get that incredible “aha!” moment, going from “this was impossible” to “actually, if I change myself and my assumptions it all becomes clear”. Philosophically, that’s just how I like to approach life, that if I could just look at things the right way they’ll make sense to me. So for me, all the emotional psychology of a crime novel is sort of on a par with the puzzle psychology, because you have to change the way you look at it to see the real answer.

Do you ever feel constrained by the conventions of crime fiction, or can working within the formulaic framework be creatively liberating?

I need the constraints of crime fiction to be an engine for my plot, because without them I’ll just wander around commenting on this relationship or that character, or this interesting observation of setting. Those are the things that delight me and excite me, but without the engine of plot, they wouldn’t all be linked and there wouldn’t be a reason to charge through and encounter all of the things that I find interesting. So I absolutely need it, or all the little things I find interesting would just be disconnected and scattered on the table.

Would you agree with Ian Rankin who said he discovered that everything he wanted to say about the world could be said in a crime novel?

Oh yes, absolutely. I think part of it depends on what people think of when they say crime novel. If somebody is very rigid in saying a crime novel is a Sherlock Holmes story and that’s it, yes, then obviously there would be some things you couldn’t explore through that character or that format, however wonderful it is. But if you have a broad idea about crime, then yes, you have the freedom to do whatever you want. Crime to me is just something serious and terrible happened and humans react. That’s very broadly applicable.

You have a very distinctive style. When and how did your authorial voice develop?

I originally trained as an actor which I loved, and one of the things that I found fascinating as an actor was that when you play one character it’s your responsibility to defend that character’s corner, and the other actors are defending their characters; all of that works together. You the actor don’t need to try to be the director. You don’t need to try to do anybody else’s part, you just do your part and that helps the others do their parts because then they have something to play off of.

So it was very natural to me to try first person first. I like stepping into a character and being limited to what they can see. To me that opens up so much depth, because the limitations themselves tell you about this character. Then when I was writing I ran into something that I wanted the reader to know that my first character wouldn’t be able to tell them. I realised I would have to change to another character at that point—page 60—and, because I like symmetry, for that book I decided well, I guess I’ll have five narrators then, because it’s a 300 page book. It made me happy to be able to explore so many different voices, so I’ve continued to do that.

Do you have a daily writing routine?

No, not at all, not at all! I’m a big believer in there being phases to writing a book. And you know, sometimes you’re doing more thinking than writing. I believe daydreaming is a huge part of writing work, and I’m always encouraging my students to count daydreaming as “I worked today”. It’s a completely necessary stage, and to denigrate yourself when you’re doing that part, to say, “Oh, I’m so lazy, I’m so terrible” I just don’t think that’s healthy. It’s vital to recognise that there’s so much that goes into creating a book besides typing. So sometimes my work is the actual writing and sometimes it’s thinking and sometimes it’s rereading and revising. There are lots of different stages.

My kids are 16 and 20 now, but when I started writing my first novel my younger son was six months old and my older son had just turned 5. We were home schooling so my life was a lot of childcare and then writing when I could. It was great that my husband’s work schedule made it so we could share the home schooling equally, so I had writing slots set aside for me during the week. But I didn’t always use them for writing because there’s a transition, there’s a ramping up to get into the writing brain.

If I had, say, four hours to write that day, I might spend three hours idly reading things or watching something and thinking and daydreaming. And then I’d write for just the last hour because I needed to use that time before to get my brain into the right place. And I did beat myself up about that and wonder if I’m a lazy and terrible person, but I don’t think I am. I think that’s just how my brain works, and now I respect it. If I sit down to take three hours for that transition, then that’s what it takes. That’s how I get my brain to do what it does, and that’s allowed.

Do you type, write by hand or use a dictaphone?

Obviously in the old days I used to write by hand because computers weren’t a thing when I was young; we hand wrote our homework or typed it on a typewriter. Now I’m all about the computer keyboard and my handwriting is a mess. I don’t think I could dictate; I have a different voice in my hands. My speaking voice is different from my typing or hand writing voice.

Do you need to have everything plotted in your head before you even start a book?

Absolutely not! I sometimes do events with Sophie Hannah and she is an amazing planner. I once saw one of her outlines for a new Poirot book, and it was 60 pages, just the outline! Then she sits down and writes what she planned to write and that works amazingly for her. When we do events, this question always comes up and we’re a nice contrast because I don’t plan at all. I often don’t even know who committed the crime or what the amazing answer is going to be. I’m in the shoes of the detective and the others looking around going, “I don’t know what happened, but I’m determined to find out!” I, along with my characters, am doing everything I can in the story to figure it out because I don’t know it either. The reader gets to join us in that adventure.

How do you keep track of all the intricacies of your plots and characters?

That’s challenging! I said I don’t plan and I don’t plan beforehand. But I often write an outline at the midpoint to analyse what I’ve written, and it gives me a nice chart where I can see, okay, these are the characters I’m dealing with, these are the different subplots they’re enacting, these are the mysteries raised that still need an answer. I turn it all into some very complex chart and often outline from that point to the end. So yes, I do need to outline, but later in the process. I do it either at the midpoint or after I’ve finished a whole first draft, to see what I’ve really done and to ask myself what I need to do to make this a satisfying book.

Do you seed clues into your plots for the reader so that they can try and solve the mystery themselves? Or do you withhold information and misdirect them so that they can’t?

A lot of people are sceptical that it’s even possible to have a satisfying ending if you haven’t planned it from the beginning. The example I always bring up is, let’s imagine that in chapter one a character stumbles, knocks over an umbrella stand and an umbrella falls behind the couch; then in the last chapter they’re being cornered by the villain and they’re able to reach under the couch, pull out the umbrella and defend themselves, okay? It could be that a planner was writing this book and they knew they would need that umbrella in the last chapter, so they deliberately set up that umbrella drop in act one, that clumsiness. Equally, if you were me, you had the clumsiness for some other reason entirely—trying to demonstrate something about their character or about a relationship or their reaction to a piece of news—and then in the end, when my character is cornered and trying to figure out how to defend themselves from the villain, I just look around and remember, oh, there’s an umbrella under the couch. I guess it’s like the difference between creationism and evolution! You know, was it all planned in advance and this was designed to be this way? Or is this just what happened to happen and each step along the way you just use what’s there? Either way can work.

As an American living in Cambridge, do you feel that coming from a different culture gives you a particular insight into life here, which then informs your work?

One of the things that’s nice about Cambridge is that it’s inherently full of foreigners, because of the University, and it’s constantly refilled by new foreigners every year. So being a foreigner in Cambridge in a way makes you a typical Cambridge person. I never feel like I don’t belong here.

And being here helped me finally write my first novel. Before I came here, when I was trying to write a novel for years, setting was a real struggle for me. If I tried to write about someplace I knew really well, I didn’t have any perspective on it. I was so deep within it I didn’t know what to say about it; it was just the air I breathed.

Then when I came to Cambridge, it was completely different from any place else, so it was very obvious to me what I wanted to tell people about it. It was also a place I was living in so I had access to knowing about it experientially in a way that I wouldn’t if I had chosen someplace I didn’t know at all. That combination of having access to know it well, while at the same time it being new to me, was what enabled me to finally write a novel. I was simply not able to do it before then.

Do you read other crime writers or avoid reading them?

I do read crime, but I avoid reading books set in Cambridge. My terror is that if I read books set in Cambridge, either I’ll subconsciously pick something up and copy it, or I’ll be so afraid that I’ve inadvertently picked something up, that I’ll feel frozen in my own writing. So I try to write about Cambridge from life, from my experience and others’ experiences, and avoid Cambridge books.

As for what I do read: I teach novel writing and crime writing at Madingley Hall, which is wonderful. So, much of my reading is either great books from the reading lists for discussion, or reading student work. Unrelated to the teaching, I read my friends’ manuscripts, which is a joy. I have a lot of writer friends and we read each other’s work and comment on it, help each other out. When it comes to reading published books I’m always either reading them just before they come out because a friend wrote them, or I’m reading them way after the fact, like “that bestseller came out 15 years ago and I’m now reading it so I can talk about it with my students” sort of thing. I’m a combination of ahead of the cutting edge and simultaneously way behind it!

Is most of your reading time used for research purposes?

No. I did an absolute ton of research when I started, research about Cambridge, research about Cambridge police. I spent a lot of time, and I have shelves of books on the topic, but now I know the foundational stuff enough that usually my research is more talking to people. That’s in fact one of the greatest things about writing novels: you get to email an expert and say I’d like to know more about what you do, could we meet up? And in Cambridge most of the time people say yes, and they’ll just explain to you how their job works. So if my character’s an astronomer and they’re studying red shift, I would ask what would that be like? Is this an accurate description of what they do? What would their day be like?

And you can even ask a question like “If you were going to commit a murder in this building, where would be a good place to do that?” People have great answers! One time I sent an email to a lock keeper out in the Fens to ask “If I wanted a body to wash up at point A would point B be a reasonable place to put it in the water?” And they were very helpful. (The answer was yes.)

And have you spoken to police officers about their work?

I met with police twice. In my second book, The Start of Everything, there are scenes of the detectives in the police station. I wasn’t sure where Major Crimes was based, just that it wasn’t in the local station, so I needed to speak with someone. (He was very gracious, though the first time I went to meet him I got turned away because he was attending to a shooting! I had to reschedule.)

In a later book my detective Morris leaves policing after an injury because he can’t function as he was used to functioning. When I wanted to bring him back, I wanted him to be in a different role; what you never want is to just have it not matter that he left. I wanted it to transform him. So a very kind detective came to my house to discuss what the options are for a police person who has had medical issues and wants to come back, and how that could transform their work. He was great, and very helpful.

If and when you get the time, what do you read for pleasure and relaxation?

I do a lot of puzzles still. Games magazine that you mentioned, which came into existence in the mid 70s or maybe late 70s. I was reading it since I was nine or ten because my dad subscribed; I still have a subscription today! At-home escape rooms and point-and-click games are a big part of my life, that sort of thing. So that’s where a lot of my “reading” is right now, in interactive story experiences.

Do you think you need to have a particular kind of brain for puzzle solving like that?

I think it’s probably a mathematical brain. It has become less mathematical as I’ve gotten older; it turns out I have difficulty solving some of the puzzles I wrote when I was younger! What’s quite fun is my husband is also good at puzzles. When we’re working together, and my sons as well, we ask each other for help; instead of just giving each other the answer we give each other hints, give nudges instead of giving it away. It’s a very social and interactive experience.

Do you find with puzzle solving that if you go away for an hour or so, then come back, the answer’s just there, as if your brain has been processing it subconsciously?

Yes, yes! And that’s what I’m saying about daydreaming and writing. Sometimes the dough of an idea needs to rise, and you’re not being a lazy baker if you take the time for that to happen.

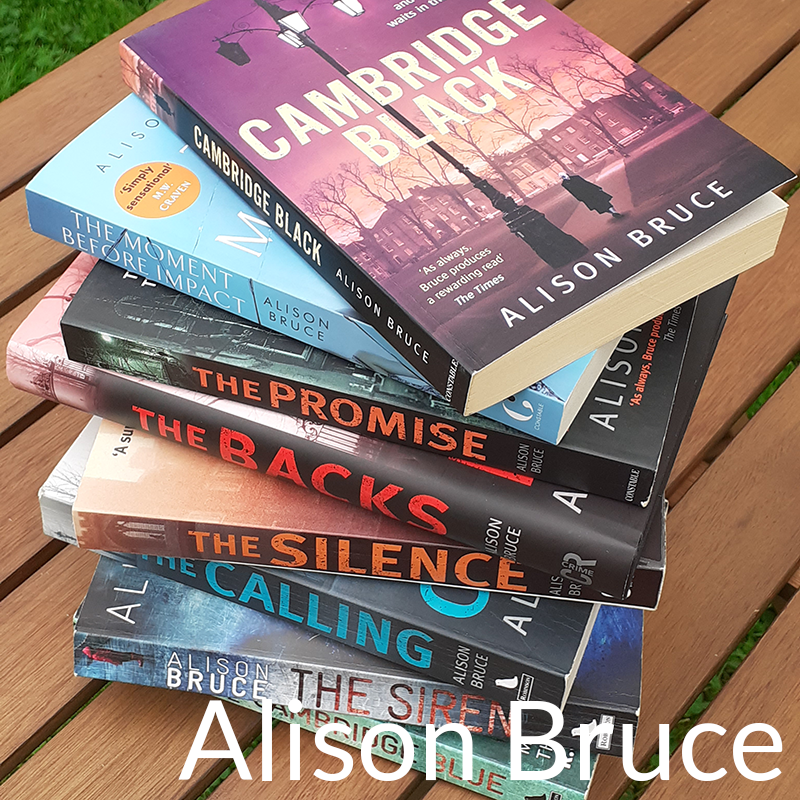

Contributor: Alison Bruce

Contributor: Alison Bruce