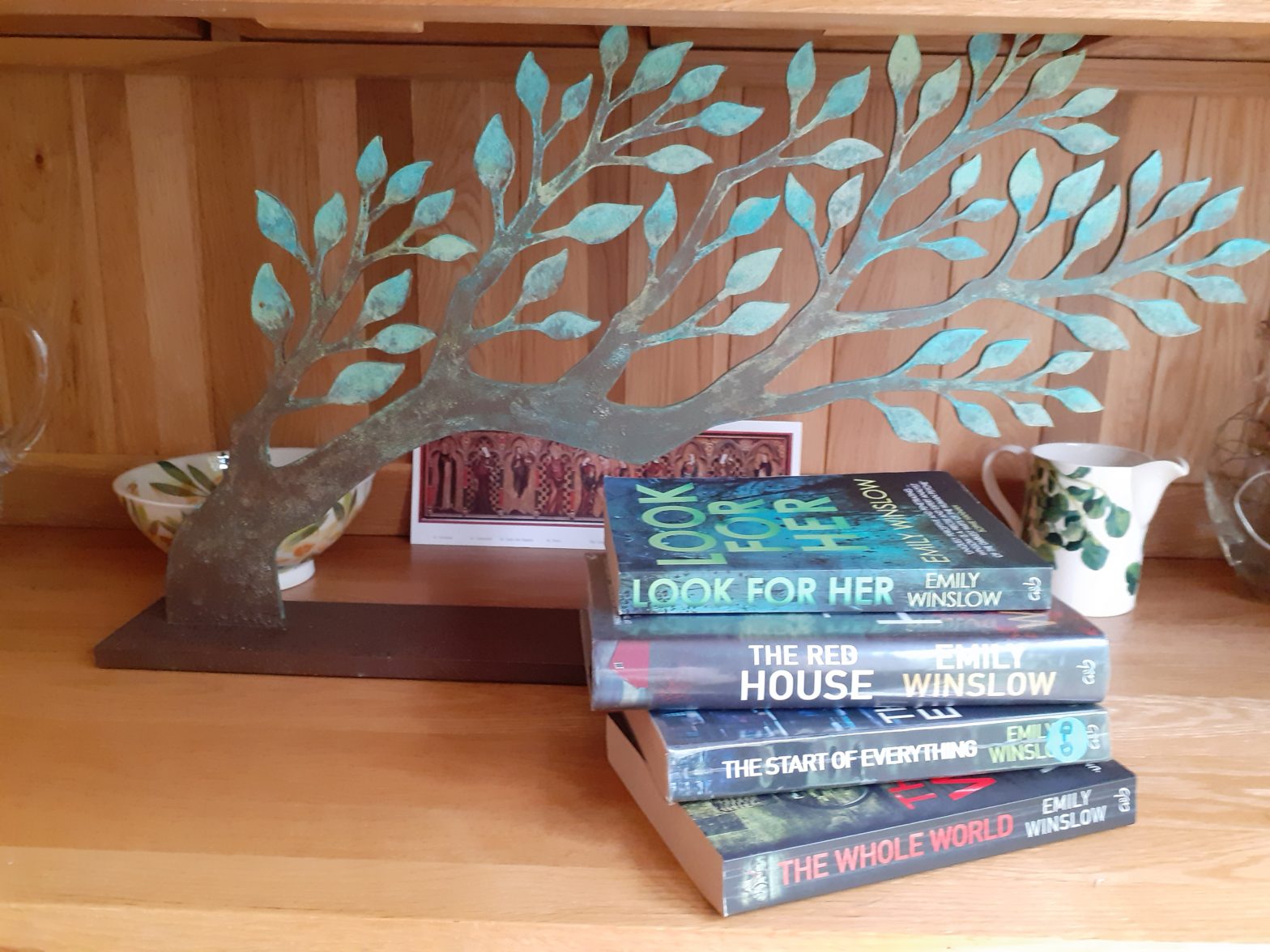

Emily Winslow, with her multiple narrators (reminiscent of Wilkie Collins’ great detective novel of 1868, The Moonstone) has introduced an unusual and distinctive voice into the world of contemporary crime fiction.

Category: Rosalind Esche

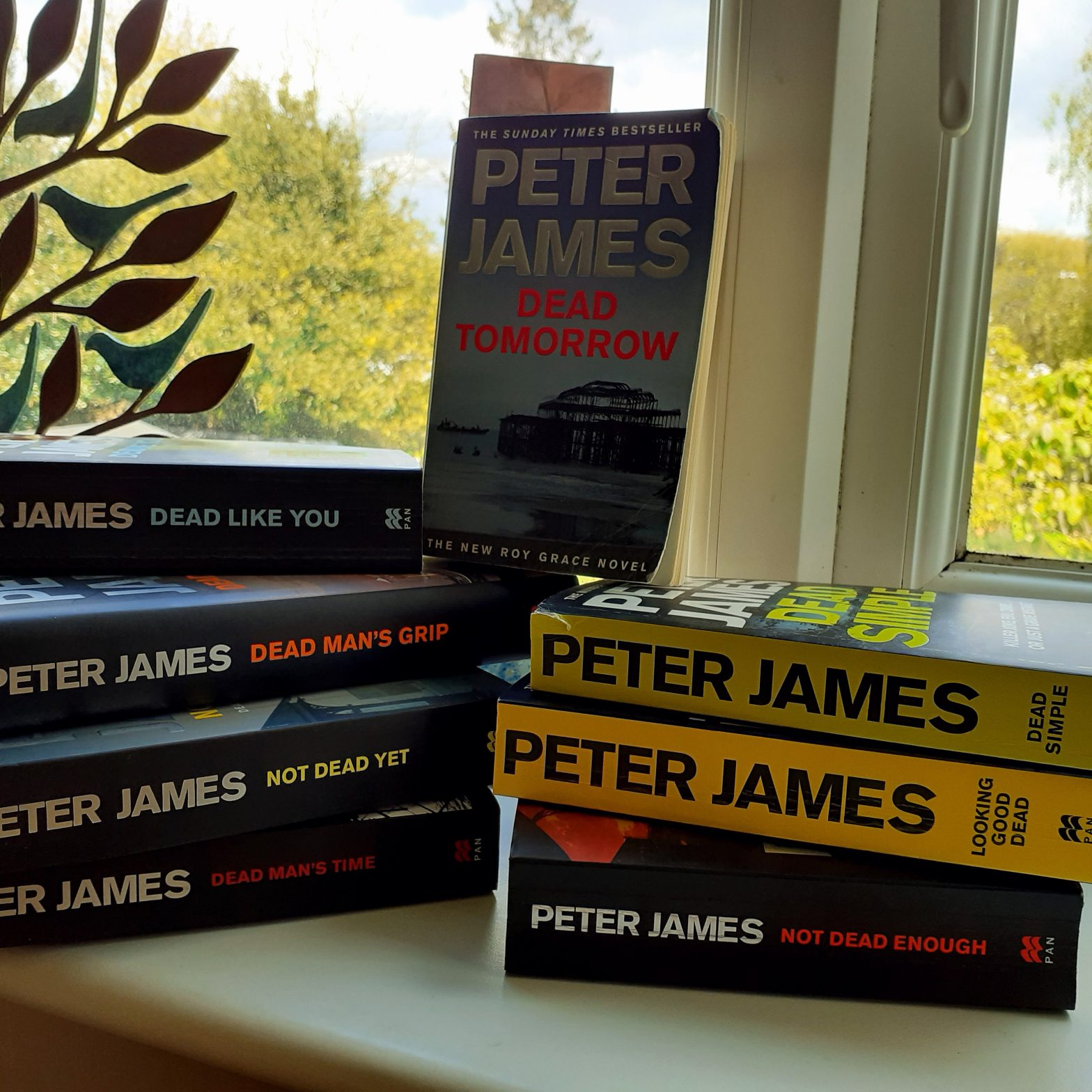

Grace

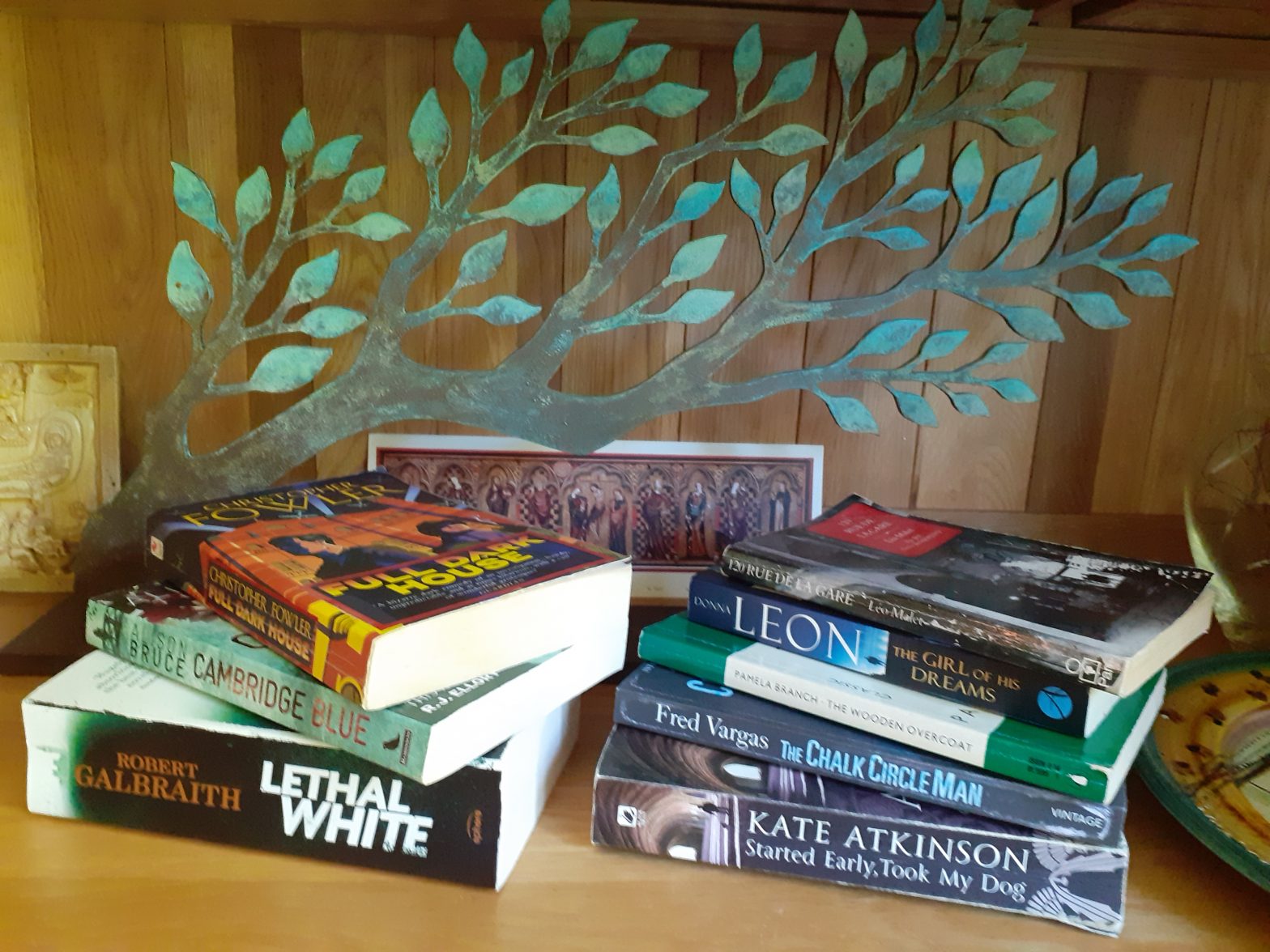

At the beginning of lockdown in the spring of 2020 I thought I would make use of the extra time at home to catch up on my ever growing, and increasingly daunting ‘to be read’ pile

Why Do We Read Detective Novels?

‘Crime fiction confirms our belief, despite some evidence to the contrary, that we live in a rational, comprehensible, and moral universe.’ – P. D. James

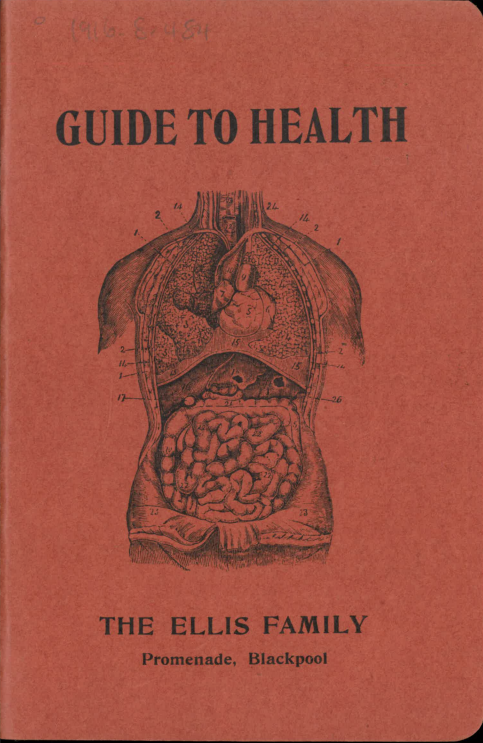

A Family of Phrenologists

When we think of seaside promenade attractions, such as fortune-telling, palm-reading and so forth, we tend to imagine stripey booths and bead curtains.

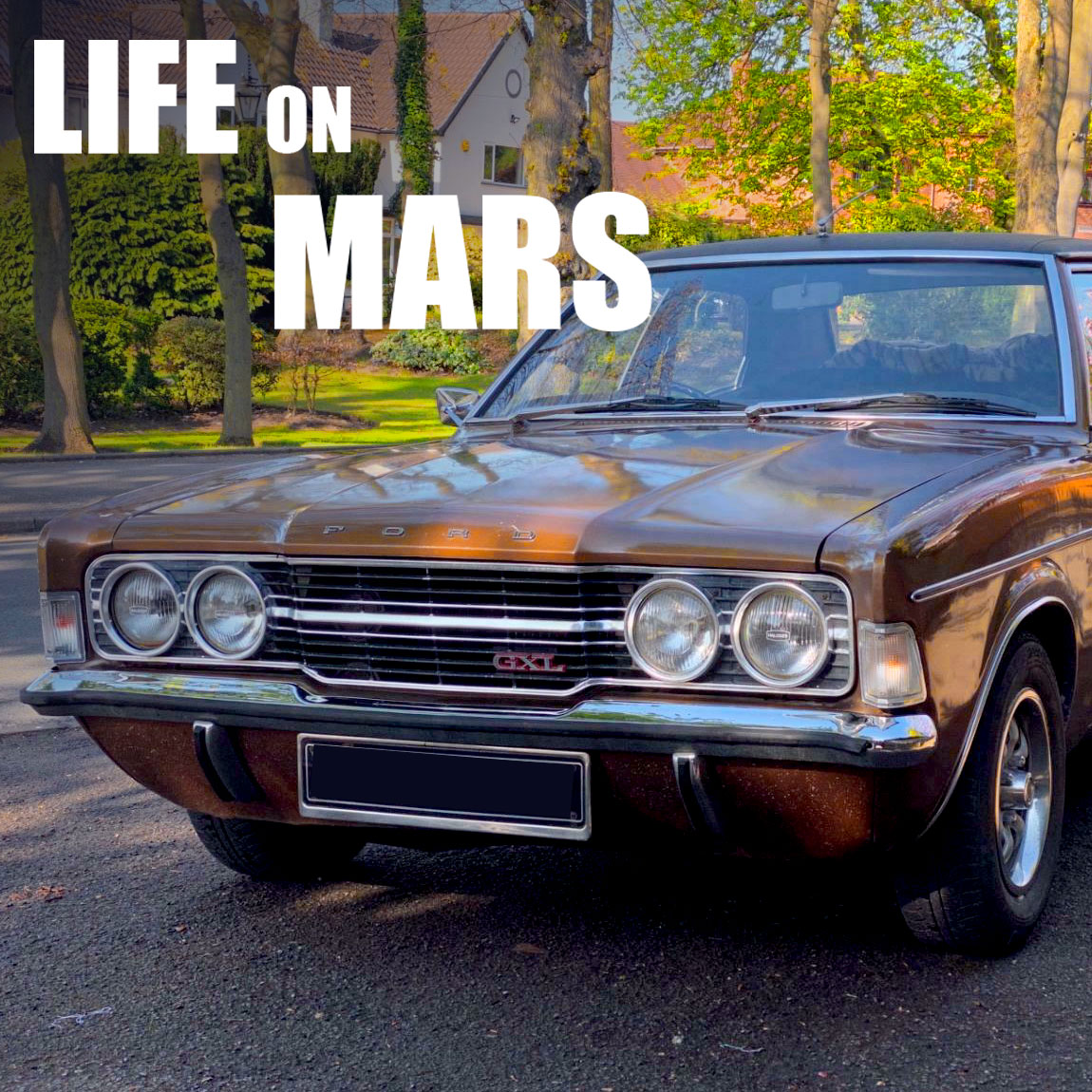

Life on Mars

The thing that has kept me going during all three lockdowns has been the British tv drama series Life on Mars, first unleashed on our tv screens 15 years ago in January 2006. I somehow managed to miss it then, but discovered it, thanks to my son, during the first lockdown during the spring of 2020.

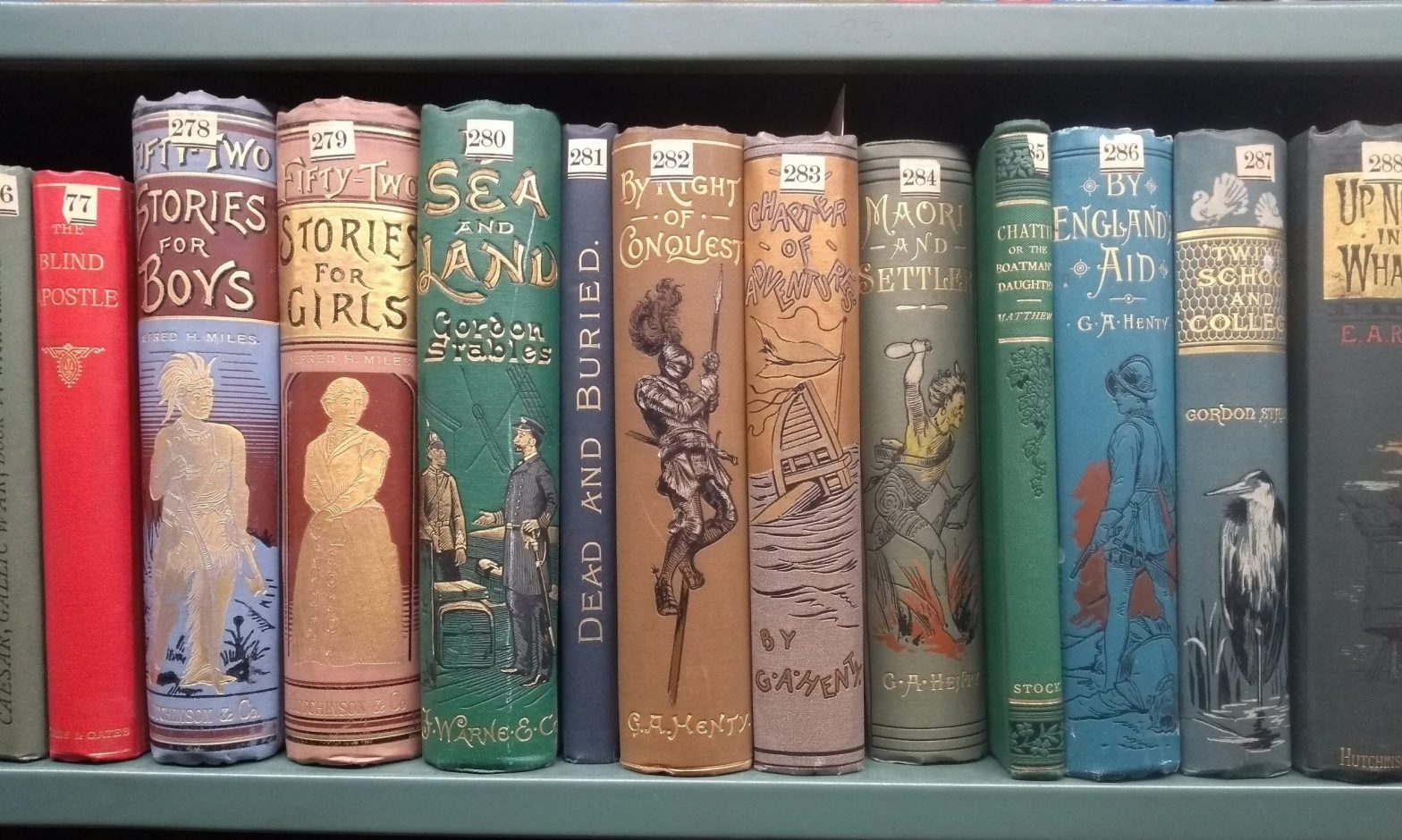

Discovering Tower Treasures

What’s really housed in Cambridge University Library’s fabled 17 storey tower? Contrary to a popular notion among students, the tower is not packed with pornography (Neville Chamberlain did rather unfortunately refer to the tower as ‘this magnificent erection’) but you might be surprised to learn that it houses a remarkable collection of so called ‘ephemera’…

The Average Boy

“When stress of weather, or the coming of long winter evenings, or any other reason gives the indoor part of life a larger importance, this indoor handy book will be found an invaluable companion.” If your children are bored being cooped up at home under the current lockdown, this may well be the book for…